167 years of California mastodons

Some years ago I was making numerous trips to museums all over California documenting mastodon remains across the state, a project that eventually led to the description of the Pacific mastodon (Mammut pacificus). The four largest mastodon collections in the state are at the Western Science Center (where I work), the Los Angeles County Museum, the Tarpits at Rancho La Brea (part of the LA County Museum), and the Museum of Paleontology at UC Berkeley. I spent multiple days in each collection documenting their mastodon holdings.

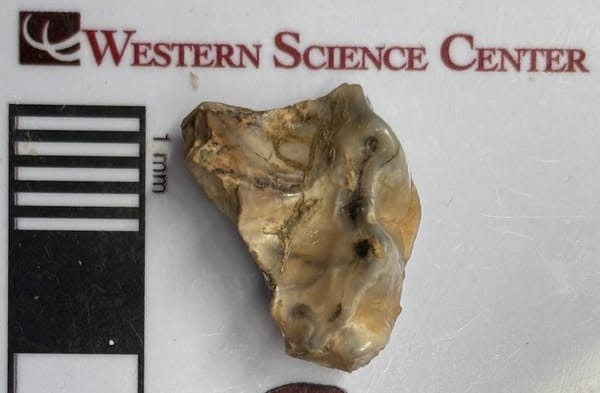

The tooth shown above is from the Berkeley collections. Even though it’s an isolated tooth, there’s quite a lot we can say about it. First, there are more than 3 enamel ridges on the occlusal (chewing surface of the tooth). That means the tooth is a 3rd molar; all the other mastodon teeth have either 2 or 3 ridges (called “lophs” if it’s an upper tooth, and “lophids” if it’s a lower tooth). And that’s not all the ridges can tell us.

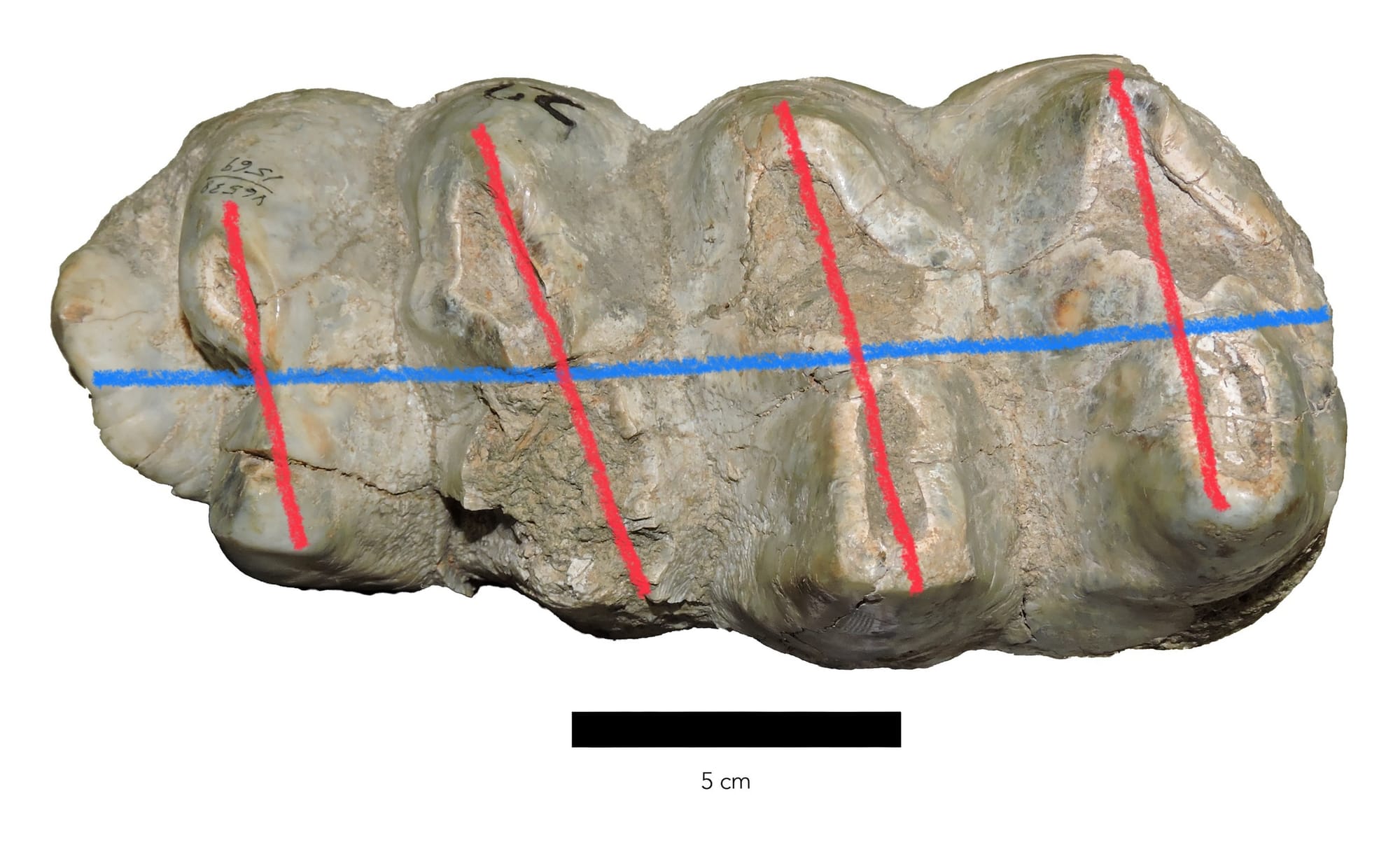

If we draw a line down the middle of the long axis of the tooth (blue line), and then draw lines through the long axes of the ridges (red lines), we can see that they don’t intersect at right angles. Unless they’re pathological, in upper teeth these intersections are pretty much always right angles, while in lower teeth (especially 3rd molars), they usually aren’t right angles. So this is a lower 3rd molar.

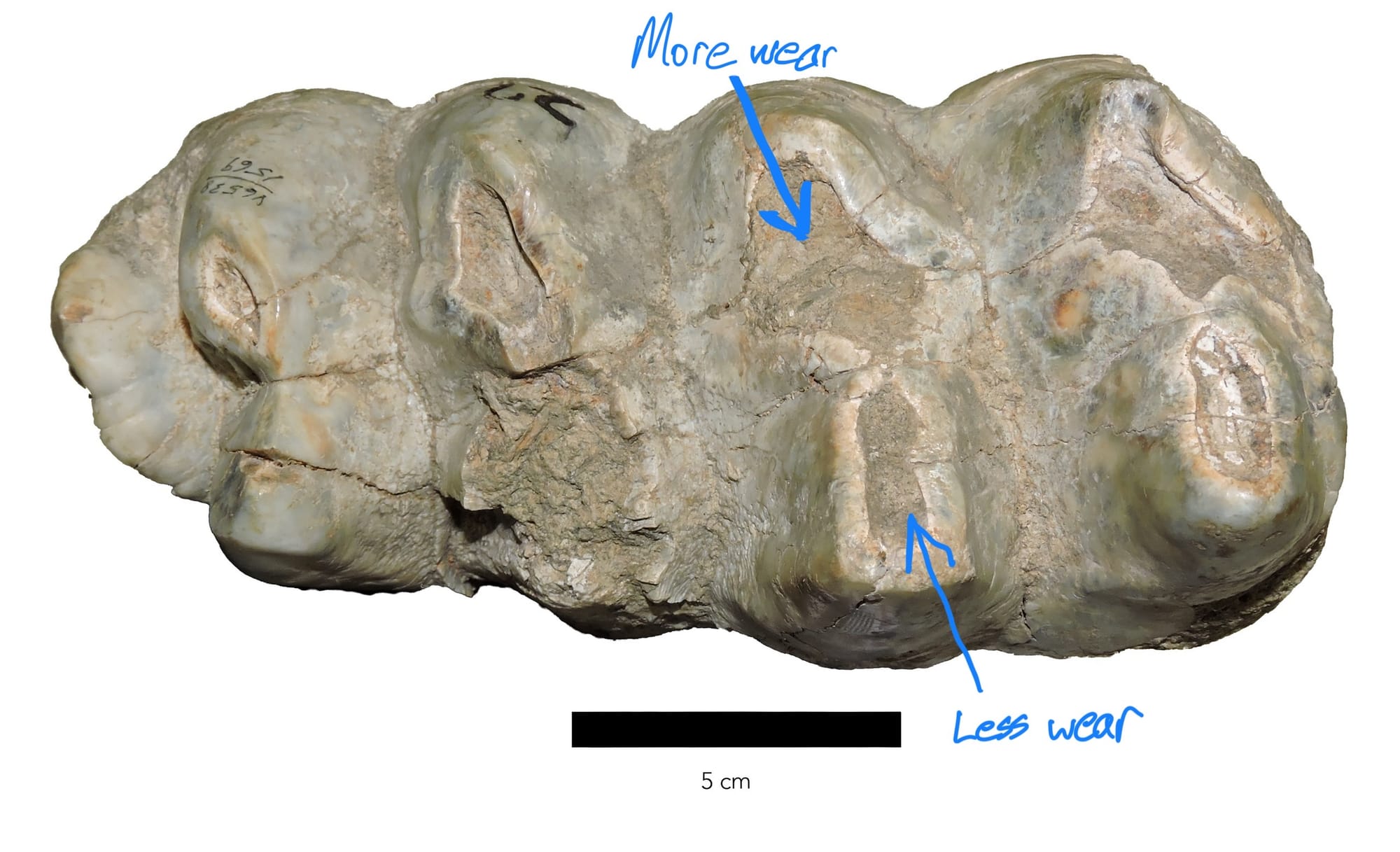

We can also see that the lophids (because now we know it’s a lower tooth) are worn more heavily on one side than the other. Because of the way mastodon teeth come together when they chew, the outsides (“labial side”) of the lower teeth wear before the insides (”lingual side”) (it’s the reverse in the upper teeth). Because this tooth is more heavily worn on the left side, it’s the lower left 3rd molar.

Finally, note that all four lophids show some wear, with only the small lophid at the back of the tooth showing none. Mastodon teeth erupt horizontally, so they wear at the front first. This means we can estimate the animal’s age at the time of death based on its tooth wear. The 3rd molar doesn’t even start to erupt in mastodons until around 32 years of age, and the entire tooth doesn’t come into wear until somewhere around age 50. So this was a fully mature, if not elderly, mastodon, probably in its late 40’s when it died.

We can also often distinguish between Pacific and American mastodons based on the length-to-width ratio of the third molars. This tooth falls squarely into the range expected for Pacific mastodons.

So that’s a lot of information from a single tooth! But that’s not why I chose to write about this particular specimen. According to its specimen label, this tooth was discovered during gold mining operations in Tuolumne County, California, in 1858, 167 years ago! As far as I’ve been able to determine, this is the very first specimen of a Pacific mastodon, or of any mastodon from California, to be placed in a museum and brought to the attention of paleontologists.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.