An intriguing tooth fragment

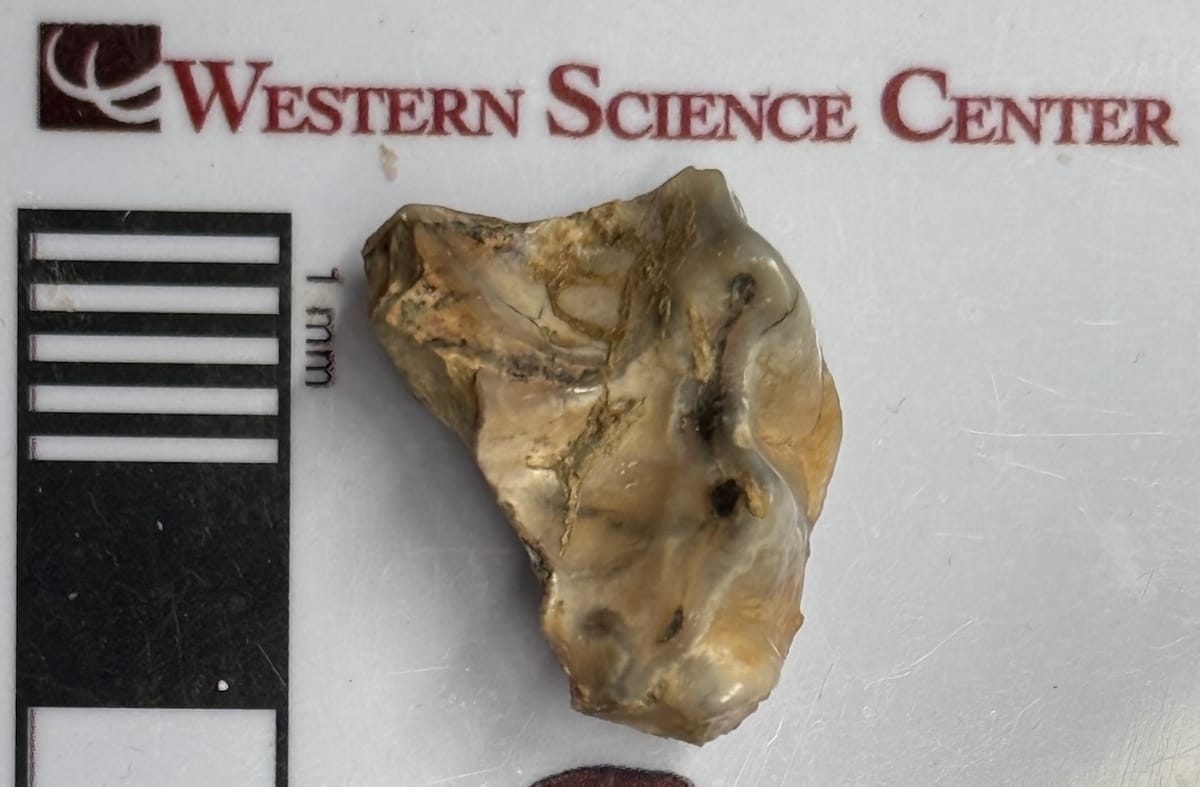

Shortly before the holidays, our curator Andrew McDonald and I were looking through one of our collections cabinets for a particular specimen from Murrieta, California. In the process we stumbled across a fragment of another tooth, recently prepared by a volunteer but not yet catalogued. Even though it was incomplete, this specimen immediately caught our attention.

After working in the Pleistocene basins of Southern California for more than a decade, I've got a pretty good idea of what fossils we're most likely to find in these deposits. Really big specimens are usually mammoths or mastodons; they dwarf all the other animals in this area. The other most likely finds are horses, bison, camels, and sloths. In the Pleistocene inland basins, if you find a bone or tooth fragment larger than a couple of centimeters there's probably an 80-90% chance it belongs to one of these six groups. Most of the remaining 10% are going to be deer, pronghorns, llama-sized camels, tapirs, and peccaries. All of the predators together are generally only a few percent of the large fossils we find (the vast predator deposits at Rancho La Brea are an anomaly unique to that site). So most of the time when we see a tooth fragment we can narrow it down to a few options right away. For example, we might not know if it's a bison or a camel, which have similar teeth, but we know it's one or the other. And that's why this tooth fragment caught our attention – at first glance, it did not appear to belong to any of the common Pleistocene animals!

Now thoroughly distracted from our original task, Andrew and I started working our way through the less likely possibilities. Deer, pronghorn, and llamas could be easily ruled out; they are related to bison and camels and have very similar tooth shapes, just smaller. All known peccaries were too small (with a 2 cm-long fragment, our mystery tooth is pretty big). We took a close look at tapirs, which were close to the right size and have been found in Murrieta. But the shape of the tooth just wasn't quite right.

So how about carnivores? No dogs (dire wolves, coyotes, etc.) have such a large tooth. The only carnivores known from the area and time period that were large enough to have a tooth this big were bears and a few of the cats, such as jaguars, sabertooths, and American lions. But this tooth had a grinding surface, a feature that is absent in cats. Could our tooth be a bear?

We have several fossil black bear (Ursus americanus) remains from Diamond Valley Lake, including several teeth. The mystery tooth is a pretty good match for the lateral side of the second upper molar:

(This is actually a 3D print of the Diamond Valley black bear; we usually do our initial identifications from replicas if they're available, to save wear and tear on the fossils.) The mystery tooth is a pretty good match except for size, as it's almost 50% larger (and the DVL black bear is a big specimen for a black bear).

There is a much larger bear from the region, the giant short-faced bear, Arctodus simus. It's known from a single incisor from Diamond Valley, and several other specimens have been reported from the region. But Arctodus is gigantic, and our molar seems to be too small for that species. So what options are left? As it turns out, we also have a replica of a grizzly bear (Ursus arctos) skull in our teaching collection:

Our tooth is only very slightly larger than our reference cast, and the morphology is a pretty good, if imperfect, match. This is potentially very exciting, as in spite of their presence on the California state flag fossil grizzly bears are exceeding rare; if this is in fact a grizzly it would be the only one in our collection! We'll be comparing our specimen to various other bears in the near future to confirm our tentative identification.

But I admit I hope it is a grizzly, because I haven't mentioned the best part. This tooth was found during the construction of a residential neighborhood, which is known as...Grizzly Ridge!

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.