Bayou Manchac mastodon

Even with only a few pieces of the skeleton, we can infer quite a lot about a mastodon that died in the Louisiana swamp thousands of years ago.

Bayou Manchac is a small body of water that flows (for lack of a better term) across the Mississippi River floodplain south of Baton Rouge. Sometime in the early 1930s, near the town of Prairieville (where today Interstate 10 crosses the bayou), Henry Howe from LSU collected some mastodon remains which are still housed at the LSU Museum of Natural Science.

The largest chunk of this mastodon was a partial lower jaw, shown above. This is dorsal view (from above), and is oriented with the front of the jaw at the top of the image. It's quite incomplete; the back third is missing entirely, as are all the teeth on the left side. Some of the teeth are preserved on the right side, and can tell us quite a lot about the animal.

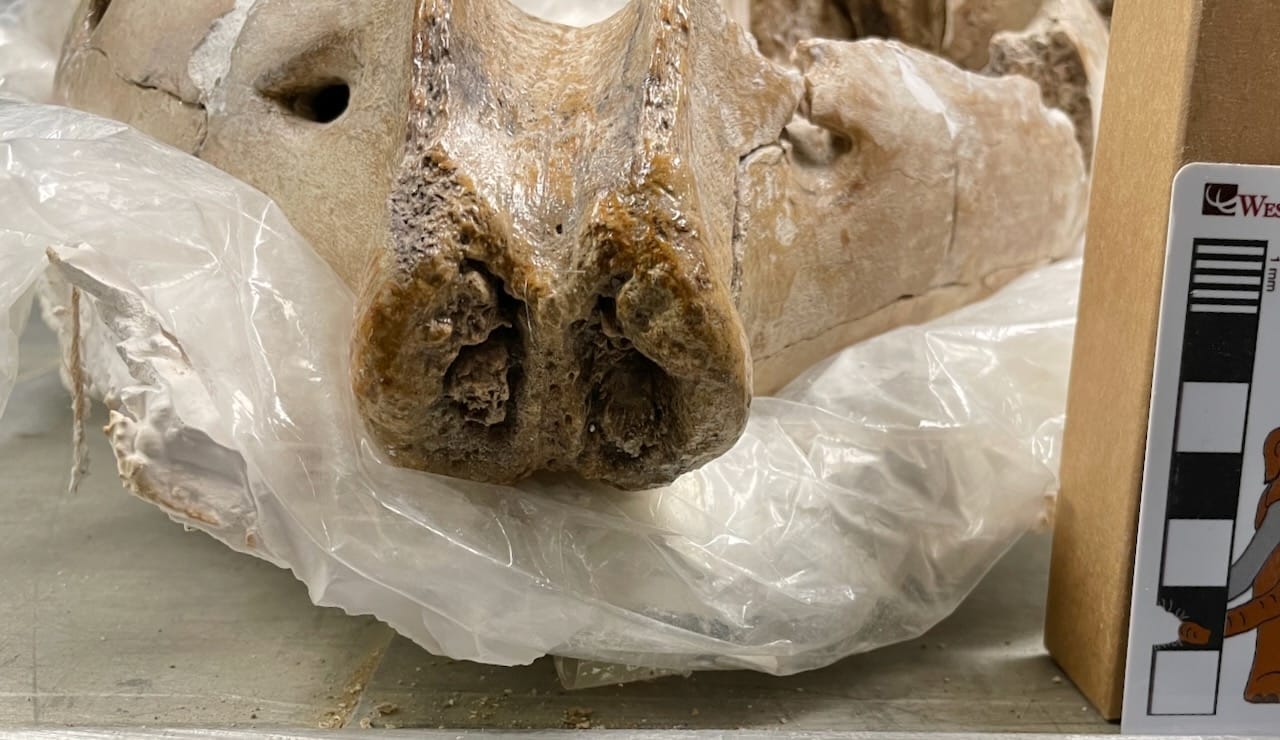

Above is a closeup of the two teeth, with anterior on the right side of the image. Each tooth is missing material at the front right corner; in the anterior tooth (on the right) this is probably natural, but on the posterior tooth this is breakage that occurred after burial. Each tooth has three lophids; these are the ridges that run transversely across the tooth. They're easily visible in the posterior tooth, but in the front tooth they've been worn down so that only their outlines are visible (and, of course, part of the front one is missing).

The presence of three lophids on each tooth is significant. Excluding tusks, mastodons only have six teeth on each side of both the upper and lower jaws, and the teeth don't all grow in at the same time. But only three of the six teeth have three lophids, the 4th premolar, the 1st molar, and the 2nd molar, so our teeth have to be two of these three. Based on their size, these teeth are the 4th premolar and the 1st molar. The 4th premolar is much more heavily worn because it erupts much earlier than the 1st molar.

In a major study published in 1966, R. M. Laws established criteria for determining the age of African elephants using skeletal features, including the wear and eruption states of teeth. This method works surprisingly well for mastodons as well, and allows us to estimate how old the Bayou Manchac mastodon was when it died. Based on the teeth, we believe this animal was around 8-10 years old, so still a juvenile (mastodons probably reached sexual maturity at around 14-16 years old).

Another interesting feature of this lower jaw is found at the anterior tip, at the chin. There are two small oval cavities partially filled with irregular bony growths. These are sockets for lower tusks. While modern elephants only have upper tusks, many ancient proboscideans had both upper and lower tusks (or in some species only lowers). Early mastodons were 4-tusked, but in Mammut americanum the lower tusks were gradually being lost. By the time the species went extinct, fewer that 25% of American mastodon had lower tusks or sockets for the tusks. The Bayou Manchac mastodon didn't have lower tusks when it died, because the sockets are partially filled with bone. But the sockets are there, and it's possible it had lower tusks earlier in its life. Interesting, these sockets also serve as an identification feature; While about 1 in 4 Mammut americanum have lower tusk sockets, no specimen of the related Pacific mastodon (Mammut pacificus) has ever been found with lower tusk sockets.

Besides the lower jaw, a few pieces from the cranium were also recovered. Above are three views of the upper right 2nd molar. Notice that the three lophs (lophs in upper teeth, lophids in lower teeth) are completely unworn? This tooth erupts later than the 1st molar and would have still been completely surrounded by bone when the animal died. The tooth wasn't even completely formed yet; while the enamel crown is complete, the roots and interior dentine were still developing and so weren't preserved.

The tip of one of the upper tusks was also recovered. We know it's only the tip because when we look at the broken end there is no trace of a pulp cavity. The tusk grows from the base, so the part of the tusk closest to the skull has a prominent pulp cavity. This fragment is way out at the tip where the tusk had stopped growing. The tip is rounded and beveled; the mastodon has worn down the tip by rubbing it against trees, digging in the dirt, or any of the other things that elephants do with their tusks.

Even with only a few pieces of the skeleton, we can infer quite a lot about this baby mastodon that died in the Louisiana swamp thousands of years ago.

For information about this and other Louisiana mastodons, check out Vertebrate Fossils of Louisiana. This specimen is figured and briefly discussed in Chapter 16.

Reference: Laws, R. M., 1966. Age criteria for the African elephant: Loxodonta a. africana. African Journal of Ecology 4:1-37.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.