Big fossil whelk

This October Western Science Center is opening a new temporary exhibit, Life in the Slow Lane: The Secret Lives of Snails and Slugs. As the title implies, we'll be looking at all things gastropods, including their diversity, behavior, and fossil record. I love doing this kind of exhibit because it gives me the opportunity to learn all kinds of things about organisms that are outside of my usual areas of study. I'll be sharing some of what I’ve learned (and previewing specimens from the exhibit) in upcoming posts.

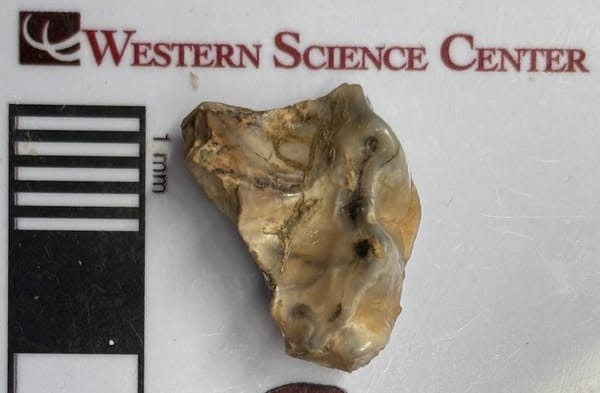

There used to be a quarry near Chuckatuck, Virginia that exposed Late Pliocene marine sediments, specifically the Moore House Member of the Yorktown Formation, about 3.5 million years old. This site was absolutely spectacular for its abundance and diversity of mollusks, with hundreds of species large and small. One of the most spectacular is the large whelk Busycon maximum, shown in dorsal view above and ventral view below:

Whelks are fascinating animals (that's true of a lot of gastropods, which is why we're doing the exhibit). Since snails usually move slowly, it can be hard to think of them as active, voracious predators, but whelks are among the many carnivorous snail groups. Among their preferred prey items are bivalve mollusks like clams.

Whelks crawl on or burrow into the mud looking for clams and other bivalves, which they can detect in part by sniffing them out with their antennae. When they find one, they will use their muscular foot to grab the clam and hold it in place.

Clams, of course, have their own shells for protection; when a whelk or other predator catches them, they'll clamp their shells closed. But this doesn't deter the whelk. The edge of its aperture (the right edge of the large opening in the image above) is particularly thick and strong in whelks. The whelk will try to insert this between the two halves of the clam shell and use it like a crowbar to try to pry the shells apart. If this doesn't work, because the gap it too small or the clam is too strong, the whelk will use the edge of its aperture like a saw, and try to grind its way into the gap. Once it's able to pry the clam shells apart, it will then eat the clam out of its own shell.

Busycon maximum is a fairly large whelk, and with a length of about 20 cm this may be the largest intact gastropod I've ever collected. But whelks can get considerably larger; the modern species Sinistrofulgar perversum can reach up to 45 cm, more than twice as large as the example shown below!

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.