Drilling for food

Some snails have to drill for their food.

The Western Science Center's exhibit on snails, “Life in the Slow Lane”, opens later this month. We'll have well over a hundred modern and fossil snail shells on display, but there will be a few shells of animals that are not snails. These include the fossil quahog clam Mercenaria corrugata from Pliocene deposits in Virginia shown above.

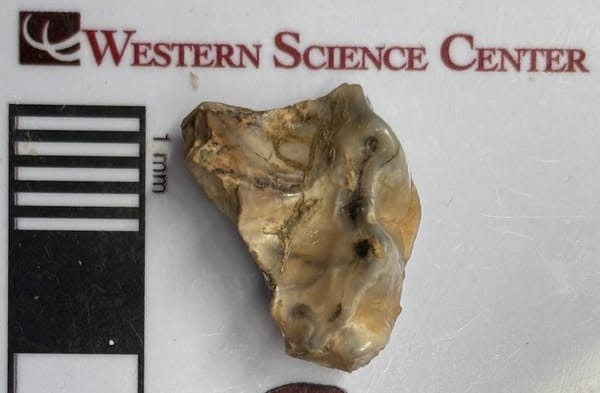

The feature that justifies the inclusion of this clam in a snail exhibit is the small hole near the shell’s hinge, shown in closeup below:

We’re also including several other species of bivalve mollusks with similar holes from the same site:

The holes provide the justification for including these bivalves in a snail exhibit: these all fell victim to predatory snails!

As I mentioned in an earlier post, many snails are predators, and they have a variety of mostly terrifying ways of capturing and subduing their prey. Several different groups are drillers. Using acid and their tongue-like radula, they drill a hole through their prey’s shell to gain access to the soft parts within. The target does’t have to be a bivalve; most drilling species are perfectly happy to attack barnacles, tusk shells, crabs, or other snails, including their own species.

The holes shown above have a distinctive counter-sunk shape, which is typical of a particular family of snails, the Naticidae or moon snails. There are moon snails known from this same locality:

Different drilling families drill their holes in somewhat different ways, and do different things to the victim once the hole is completed. In the case of naticids, they inject digestive enzymes through the hole into the clam, breaking it down inside its own shell. Once the enzymes have done their work, the snail uses its proboscis like a straw to suck the digested clam through the hole.

For more details on drilling snails, check out PRI’s website Digital Atlas of Ancient Life. “Life in the Slow Lane: The Secret Lives of Snails and Slugs” opens at the Western Science Center on October 25.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.