Dropstones in the tropics

Much of this text was originally published on my old blog “Updates from the Paleontology Lab“ on February 22, 2008.

Western Science Center is located in a semi-arid basin in Southern California, a short drive from the Colorado and Mojave Deserts. It seems an odd place to spend much time thinking about glaciers. Yet the ebb and flow of glaciers has a profound impact on global climate, including here in the California desert, and as a museum responsible for public education about earth sciences we want to make sure our local community understands those connections. That’s why last summer we sent our collections manager Brittney Stoneburg off to Alaska. Brittney spent time on a research ship with a team of oceanographers studying the glacier-ocean interface in a project funded under the National Science Foundation's Polar STEAM Program. We recently opened an exhibit about this work, called Whirling and Churning: How the Ocean Melts an Alaskan Glacier, and tomorrow's monthly Science Saturday children's event is themed around glaciers.

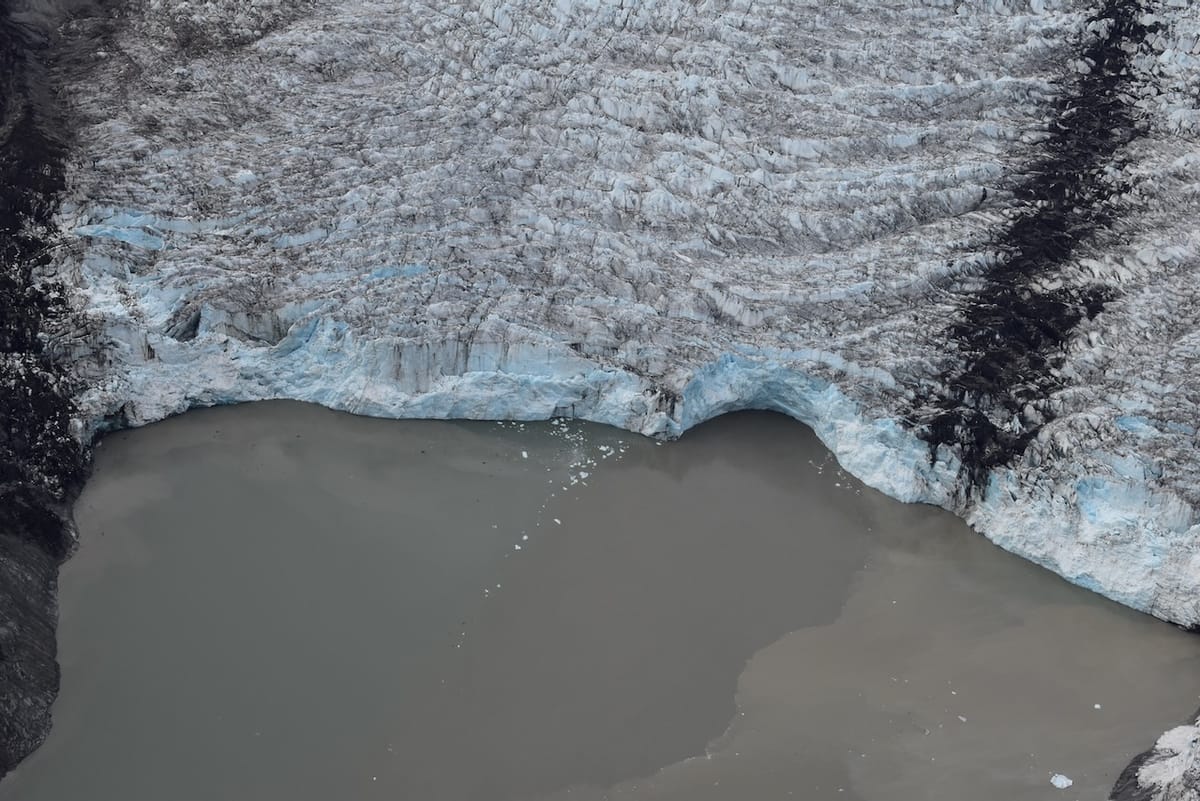

When glaciers move across the landscape they grind up a lot of rock, as can be seen in the Alaskan glacier shown above. Much of that ground-up rock ends up embedded in the glacier itself. When the glacier reaches the ocean, pieces of it break off to form icebergs which float away, occasionally running into ships but more often just floating off to warmer waters where they eventually melt. Many of those iceberg will include some of the gravel from the glacier. In the image below, sediment rich streaks are visible in the glacier in the background, while the the dark blobs in the foreground are gravel-rich icebergs.

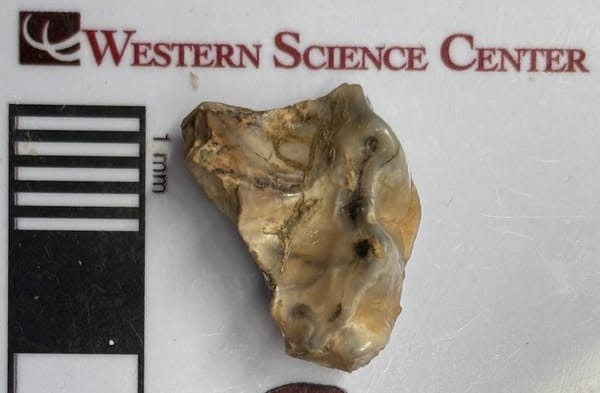

When those icebergs eventually melt, the rocks they contain will fall to the seafloor and land in whatever sediment lies beneath them, sometimes thousands of kilometers from their points of origin. The rocks are very aptly named dropstones. Since most seafloor sediments are fine-grained muds, large dropstones are easy to spot.

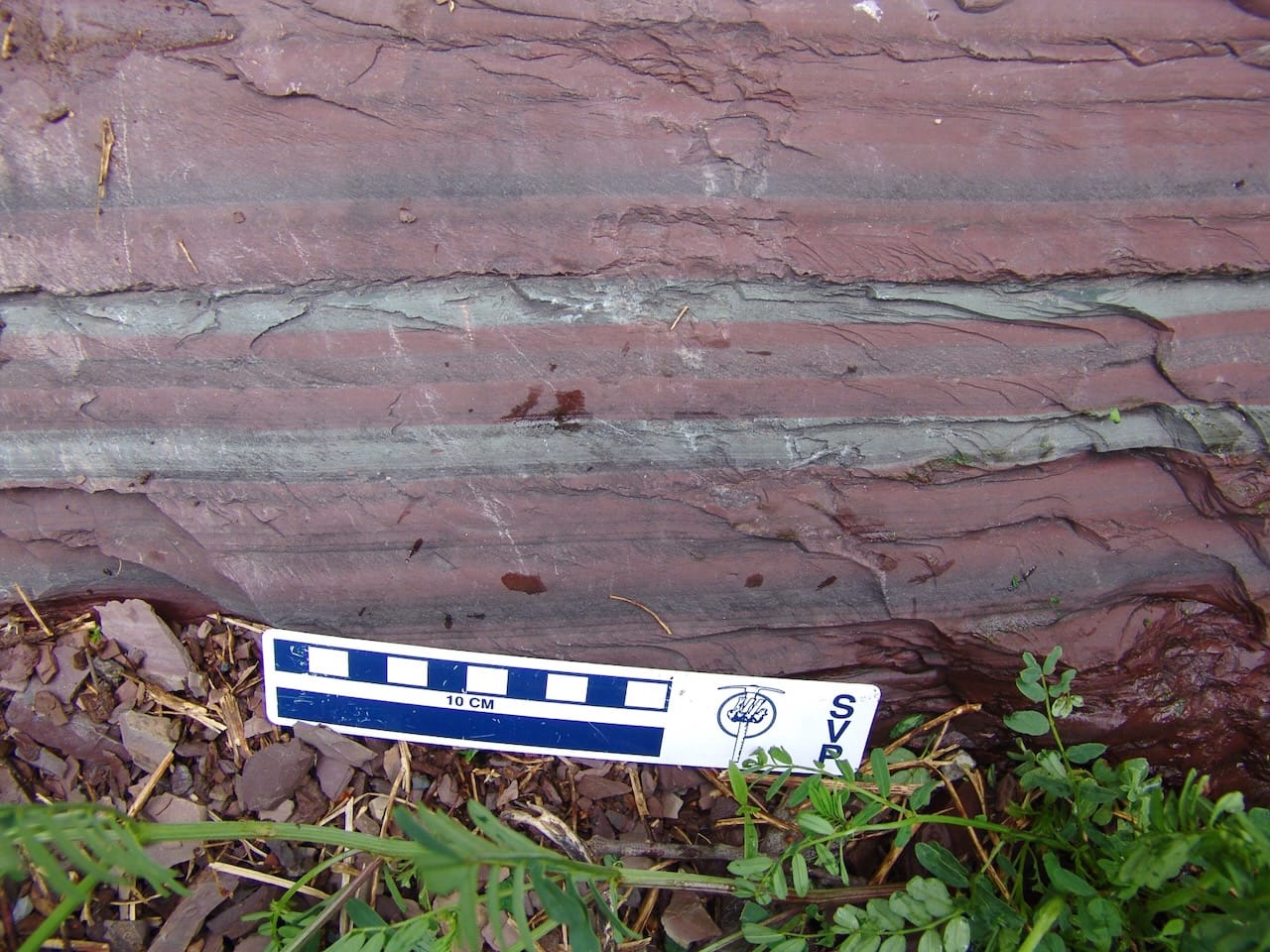

This particular dropstone is in the Konnarock Formation, a rock unit near Mt. Rogers in Virginia. The Konnarock was deposited in the late Proterozoic Eon, between 760 and 570 million years ago. It’s thought that, at that time, Virginia was pretty close to the equator.

It turns out that late Proterozoic sediments from all over the world show evidence of glacial activity. Andy Moore gave me this rock, from his backyard in Indiana. It is a tillite (another type of glacial rock), from the late Proterozoic of Canada (ironically, it was carried to Indiana by glaciers during the most recent Ice Age, around 15,000 years ago.)

The wide distribution of late Proterozoic glacial deposits led to the development of the “Snowball Earth” hypothesis. The basic theory is that the late Proterozoic experienced a runaway ice age, in which thick ice sheets covered the entire Earth. (A derivative hypothesis, “Slushball Earth”, holds that the equatorial oceans may have had semi-seasonal sea ice, like today’s Arctic Ocean.)

Snowball or Slushball Earth has had an impact on paleontology as well. One characteristic of Proterozoic sediments is that they contain almost no fossils. During the next time period, the Cambrian, there is a dramatic increase in the number of fossils, both the organisms themselves and their traces; this event is referred to as the “Cambrian Explosion”. (See the comparative images below.) Almost all the major phyla of animals first appear in the fossil record at this time. It may be that organisms were evolving in relatively isolated deep-sea environments (which don’t preserve in the rock record), and with the end of Snowball conditions they were able to rapidly move into shallow-water environments for the first time.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.