Giant mastodon from the bayou

Mastodons have been known to western scientists for more than 250 years, and were identified in Louisiana as early as 1804. But in spite of the long history of mastodon research, they still have lots of surprises for us.

Mastodons have been known to western scientists for more than 250 years, and were identified in Louisiana as early as 1804. But in spite of the long history of mastodon research, they still have lots of surprises for us.

Many of Louisiana's mastodons have been found in the Tunica Hills region, an area just east of the Mississippi River wedged between Baton Rouge to the south and the Mississippi state line to the north. This region is covered by layers of glacier-derived wind-blown sediment called loess, up to 9 meters thick. Loess forms very fertile soils and the Tunica Hills are covered in dense forests, which are not ideal for fossil collecting. But loess also erodes very easily, and the Tunica Hills are closed by numerous streams and bayous (this is the source of the topography that justifies "Hills" in the name), so Pleistocene fossils can often be found eroding out of the stream banks, albeit usually isolated teeth or individual bones. Below, I'd like to go step-by-step through the process of identifying one of these bones.

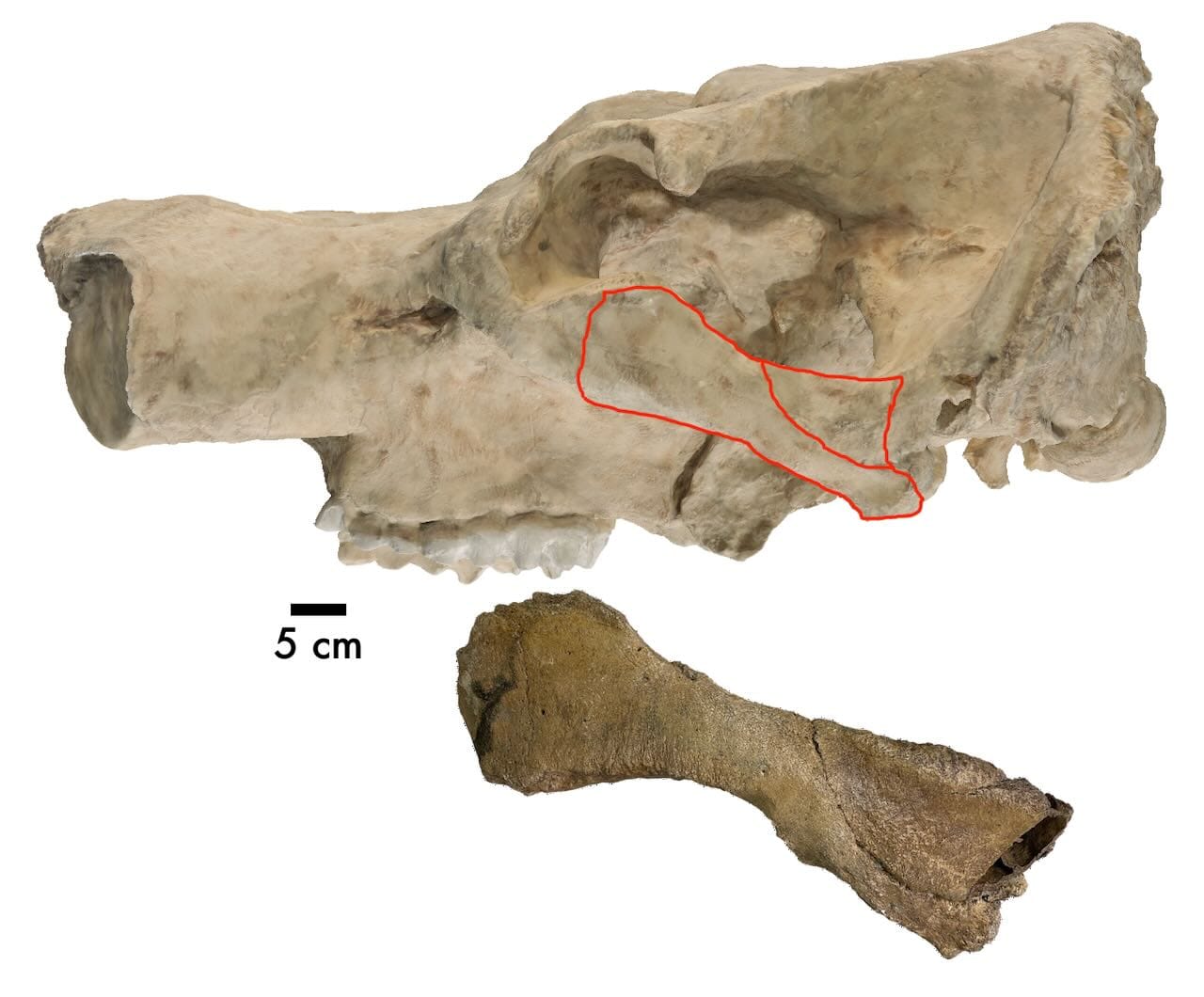

The bone shown above was found in Tunica Bayou in 1983. It's clear that it's a fragment of something larger, because of the broken surface visible on the right. There's also a noticeable curved groove that separates roughly the right third of the fragment from the left two-thirds. To someone used to looking at skeletons, that groove is a give-away; it's a suture between bones, indicating that we're actually looking at two bones.

There are other clues to help us narrow down our identification. From the accompanying scale bar, we can tell this is a pretty large fragment, about 40 cm long. Only a few Ice Age animals in North America had any bones this large: proboscideans like mammoths and mastodons, bovids like bison and musk oxen, some camels, ground sloths, some of the biggest deer, and maybe horses. Other views of the bone tell us even more:

In this view we can see the broken surfaces more clearly, Rather than being solid, there are a series of empty spaces surrounded by thin walls of bone (sinuses) that were filled with air in the living animal (in technical terms, the bone is pneumatic). This is usually a feature that serves to make very large bones lighter. Of the animals listed above, only the proboscideans and the bovids have heavily pneumatized bones (specifically, their skulls). But this bone doesn't match the shape of the pneumatized areas in any bovid skull, so it almost certainly comes from a proboscidean. Once we've narrowed the possibilities, it's not hard to find a match:

Our mystery bone is part of the left eye socket from a mastodon! Specifically, the anterior bone (the left 2/3 in the top image) is the jugal, which forms the bottom of the eye socket. The back 1/3 is the tip of the zygomatic process of the squamosal, basically the cheekbone.

I mentioned before that the Tunica Hills bone is pretty large, about 40 cm long. How does it measure up? We compared it to "Max", a mastodon skull at the Western Science Center. Max is from a different, slightly smaller species (Mammut pacificus), but he is the largest specimen known from that species. With a skull length of 1 meter (not including tusks), Max is as large as or larger than most American mastodons (Mammut americanum).

In the image above, Max's skull and the Tunica Bayou specimen are shown in the same orientation and scale. The common bones are outlined in red on Max. As is immediately obvious, the Tunica Bayou mastodon was huge! Again, Max wasn't tiny; he's an adult male, the largest known specimen of his species and the largest mastodon ever found on the west coast (about 3 meters tall), but Tunica Bayou makes him look tiny! We don't have a lot of very complete mastodon remains from Louisiana, but scraps like this hint at some true giants wandering around Louisiana during the Ice Age.

For information about this and other Louisiana mastodons, check out Vertebrate Fossils of Louisiana. This specimen is figured and briefly discussed in Chapter 16.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.