Heavy ribs

Sometimes you just have to pack on the weight.

Last week we looked at how ribs, in addition to serving as protection to the internal organs, also play a crucial role in breathing. But ribs are by no means limited to these roles, and animals may have additional specializations of the ribs to allow them to perform other functions. Marine animals that are descended from land animals are a prime example.

Tetrapods (literally "four feet") are a group vertebrates that have four limbs, two lungs, and lived on land in their ancestral forms. Over time, some of the original tetrapod characteristics have been lost in some groups as they evolved in response to new conditions; for example, snakes are tetrapods even though they only have one lung and no feet, because their ancestors were tetrapods that did have four feet and two lungs. And even though most tetrapods through history live on land, a shocking number of groups have moved back into the water and adopted an aquatic lifestyle (this happened in so many groups that every three years there is an international conference for scientists called the "Conference on Secondary Adaptations of Tetrapods to Life in the Water").

Moving back into the water presents special challenges for tetrapods, and one of the biggest is that they get oxygen from the air with lungs, rather than using gills. But drowning isn't the only issue. If you're going to live your entire life in the water, it would be nice to be able to dive, right? After all, that's where most of the food is. The problem is that tetrapods are pretty buoyant and don't like to sink. For starters, we have two giant air-filled lungs that tend to keep us afloat. And if you're warm-blooded, a good way to stay warm in the water is to wrap yourself in a blanket of fat. But fat is less dense than water, so that tends to make you float too. So you need to find some place in your body where you can add weight to make it easier to dive. And there is a whole ribcage just sitting there!

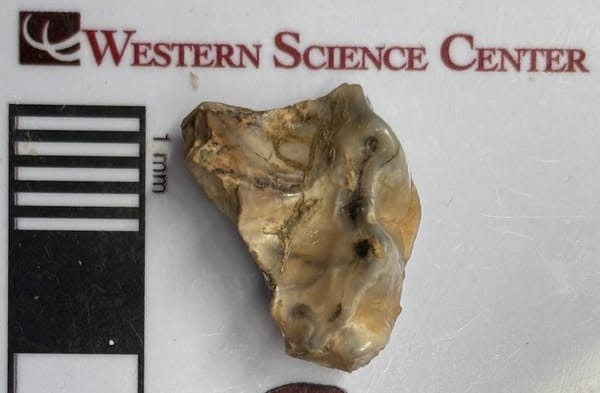

Above on the left is a cross section through a mastodon rib, and on the right is a color-coded version of the same image. The cyan-colored ring on the outer edge of the rib is composed of very dense bone called cortical bone. The purple interior is called cancellous bone. It's a lattice of very spongy and low-density bone, with red bone marrow filling the open spaces in the living animal (this is where a lot of our red blood cells are made; ribs do so many things!). But if you're a fat, air-filled animal trying to dive under water, this structure presents an opportunity to increase mass, because that cortical bone is much denser than water. So you can either pack additional cortical bone onto the outside of the rib ("pachyostosis"), or you can replace some of the low-density cancellous bone with cortical bone ("osteosclerosis").

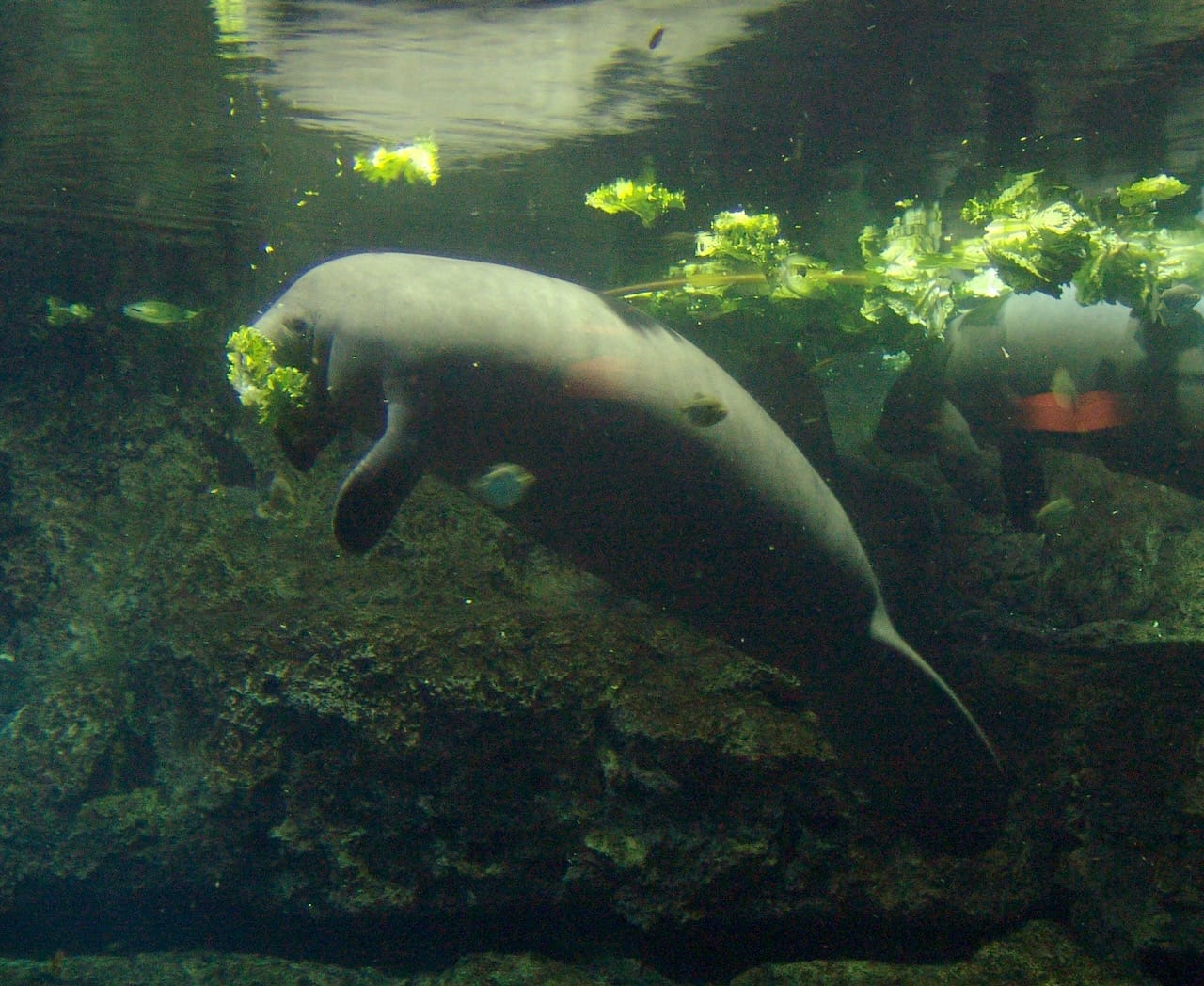

Which brings us to the sea cows. Sea cows, from the mammalian order Sirenia, returned to the ocean over 50 million years ago. There are two extant genera, the dugong (Dugong dugon) and several species of manatees (Trichechus spp.) (Florida manatee Trichechus manatus from SeaWorld shown above). As can be seen in the photo, sea cows are herbivores, the only marine mammal herbivores still in existence (there were some others that are now extinct). This presents sea cows with a special problem – they not only have to dive, but they have to stay on the bottom long enough to graze on plants growing on the seafloor, while being wrapped in buoyant fat to stay warm. To do this sea cows have gone all out on rib modifications. Here's Miosiren kocki, from the Miocene of Europe:

The ribs in most sirenians are extremely pachyostotic, with so much cortical bone added on to the outside of the ribs that they nearly touch one another. But sea cows don’t stop there. Below is a cross section through a sea cows rib:

The rib has no cancellous bone at all; it’s dense cortical bone all the way through. Sirenian ribs are pachyosteosclerotic, with cortical bone added to both the inside and the outside. While many marine mammals have dense ribs to help with buoyancy, no other groups take it to the extreme levels of sea cows.

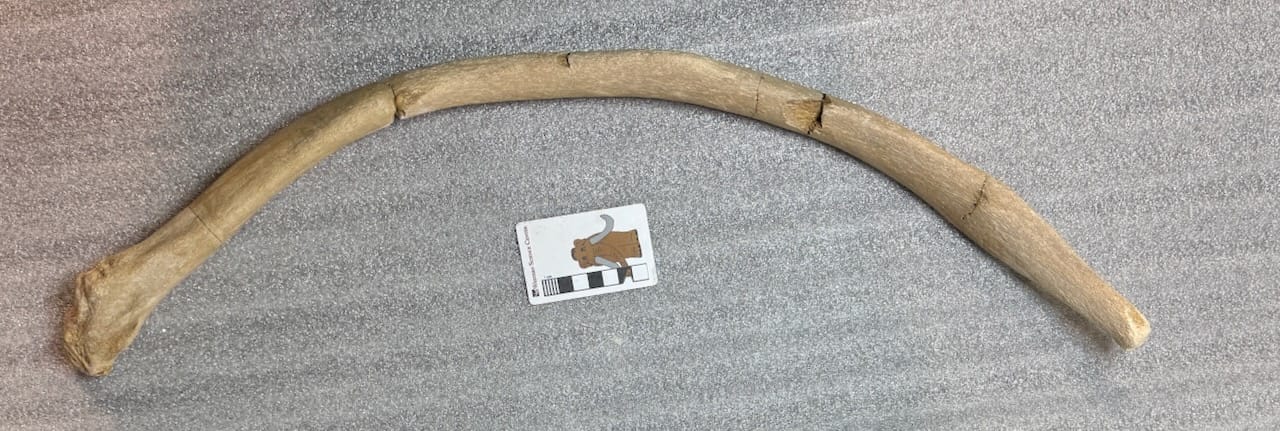

Finally, because evolution can go off in all kinds of unexpected directions, some of the last members of one subgroup of dugongs, the hydrodamalines, seem to have largely started eating kelp near the surface of the ocean. Without the need to spend long periods on the seafloor grazing, they seem to have started reversing some of the extreme pachyosteosclerosis. Below is a rib from Cuesta’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis cuestae), which doesn’t seem wildly out of proportion compared to land mammal ribs. Inside, however, it’s still cortical bone all the way through.

Cuesta’s sea cow’s apparent direct descendant was Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas, below), which survived in the Aleutian Islands until it was hunted to extinction around 1868. It’s clear in the mounted skeleton that the ribs are not nearly as thick as most other sirenians. Between reducing rib density and adding insulating fat, Steller’s sea cow had entirely lost the ability to dive, and spent it’s life at he ocean’s surface.

Next week, we’ll continue to look at the role dense ribs play in marine mammals.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.