More alligator lizards...this time with teeth!

The Western Science Center's alligator lizard (Elgaria multicarinata) moved into its new habitat earlier this week, beside our display of Pleistocene microvertebrate fossils from Diamond Valley Lake. As I mentioned last week, these lizards are native to the area, and have been for a long time. We actually have Elgaria fossils in our collection dating back to around 2 million years, although the majority of our specimens are 50,000 years or younger.

Alligator lizards are predators with a mouthful of teeth, and prey mostly on insects and other arthropods (we feed ours crickets). They are apparently significant predators of black widow spiders, and seem to be immune to black widow venom. But they aren't choosy, and will also eat slugs, small mammals, baby birds, and other lizards.

Our collection database lists several Elgaria maxillary bones. The maxillae are the bones that make up the sides of the upper jaw, and generally carry most of the upper teeth (although other bones can hold teeth as well). Many of our maxillae are listed as including teeth, so I decided to take a look.

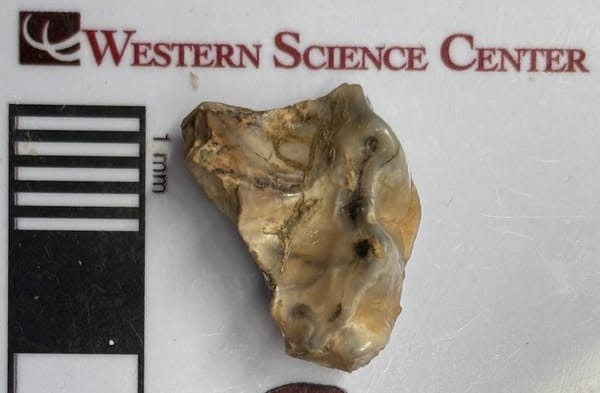

Above is the partial right maxilla of Elgaria from Diamond Valley Lake. It's shown in lateral (side) view, with the anterior end on the right. Eight teeth are visible along the bottom edge of the bone. They may not look especially sharp, but keep in mind how much this is magnified; the entire bone is only a little over 4 millimeters long!

Above is the medial (inside) view of the same bone. In this view we can see the entire length of the teeth, because the teeth are not embedded in sockets! Instead the sides of the teeth are fused along most of their lateral side to the vertical wall of bone that forms the lower edge of the maxilla. In lateral view that wall hides most of the tooth, but in medial view we can see the wall through the gaps between the teeth. The teeth don't really have much bony connection at their bases or medial surfaces, but instead just a series of ligaments that help hold them in place.

This type of tooth implantation is referred to as pleurodont, and is found in the vast majority of lizards and snakes as well as many extinct groups. It's quite different from the thecodont condition in which the teeth are embedded in sockets, as seen in mammals, dinosaurs, and crocodilians.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.