Ribs on the wing

A story of hidden fossils, microCT scanners, and a tiny dragon.

Over the last several weeks we've looked at how ribs attach to the skeleton and at their important function in breathing, as well as serving as ballast in sea cows and some whales. But that only scratches the surface of the ways ribs can be adapted for additional roles.

In my early years at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, I worked for Dr. Nick Fraser, who has long worked on Triassic faunas from around the world. A major Triassic site, the Solite Quarry, was located only 30 minutes from VMNH, so Nick and I spent a lot of time at the site splitting rocks, looking for plants, insects, fish, and a small aquatic reptile called Tanytrachelos. On one trip (I wasn't present, this happened while I was still in grad school) Nick almost tossed a rock aside, but at the last moment the light caught it just right and he saw what he thought was a coelacanth tail (there are several coelacanth species at Solite). Closer examination showed that something else was going on:

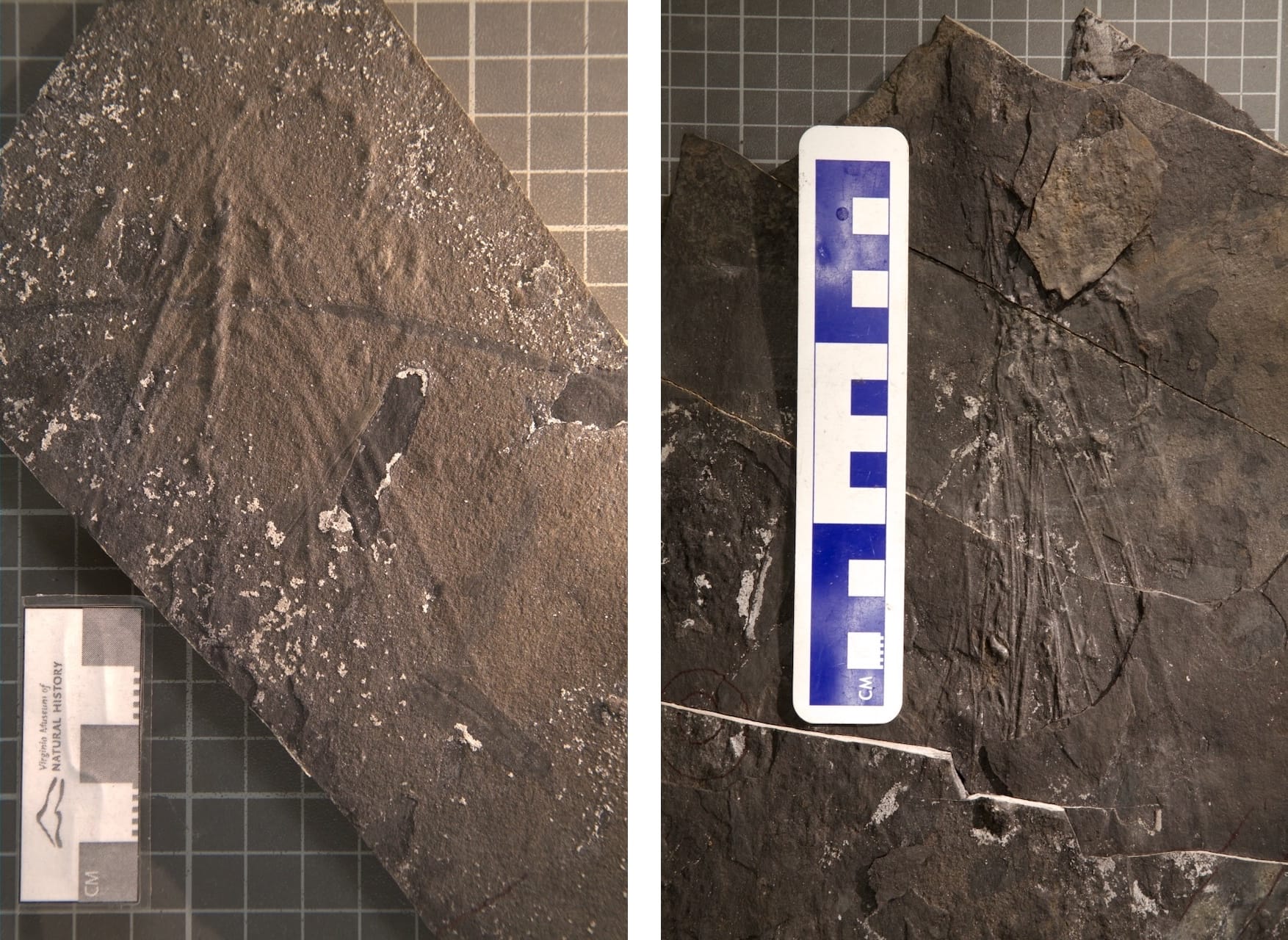

There clearly seemed to be a skeleton of a long-necked reptile, but the only long-necked reptile known from Solite was Tanytrachelos, represented by hundreds of specimens. And whatever this thing was, it seemed to have very long ribs, unlike Tanytrachelos.

A few years later, Nick discovered a possible second specimen, with almost nothing visible except the barest hints of elongate ribs:

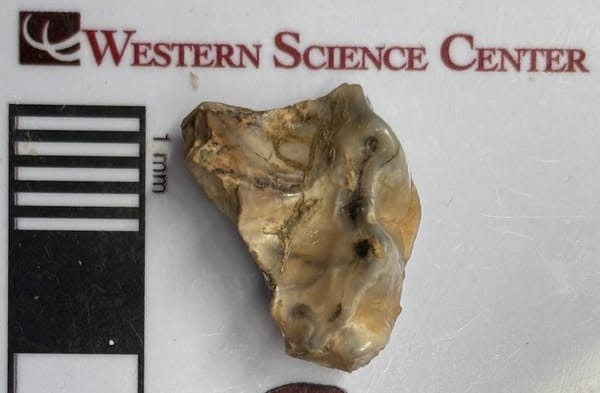

In the early 2000's both Nick and I made various attempts at preparing these specimens to see what material was hidden inside the rock, but to no avail. The Solite deposits are actually low-grade metamorphic slates, which makes the rock much harder than the fossilized bone. CT scanning using X-rays to examine internal structures had been around for several years, but medical CT scanners lacked the resolution to resolve bones that in some cases were less than 1 mm in cross section. High-resolution microCT scanning was just becoming a thing, but it was expensive and almost entirely found in industry. Only 3 or 4 universities in the US even had microCT scanners back then, but fortunately Nick was able to arrange scans of the two specimens at Penn State. The results were remarkable:

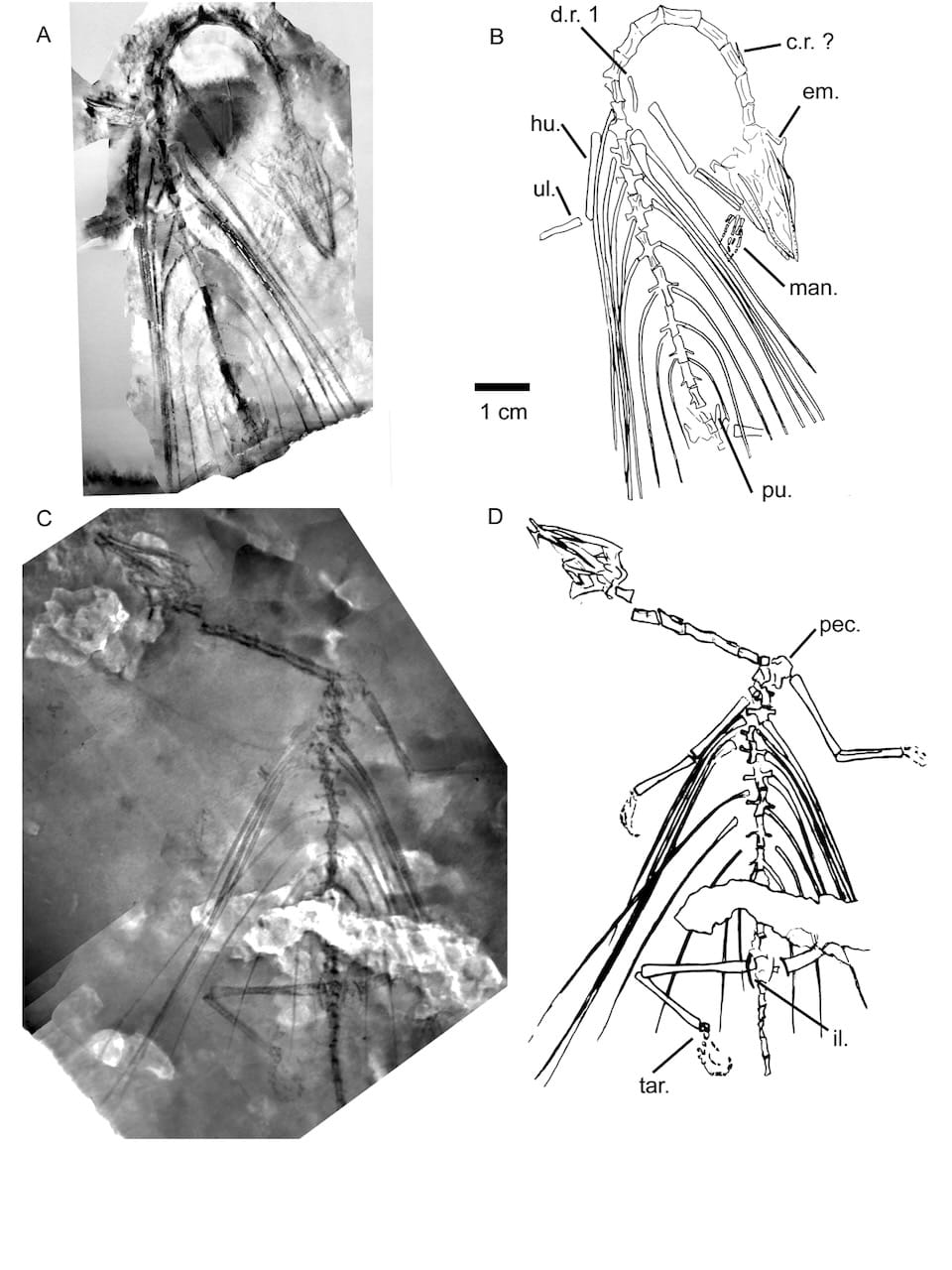

Video of the microCT scan of the holotype Mecistotrachelos apeoros. Most of the skeleton anterior to the tail is visible, including elongate ribs and vertebrae, the skull, and a complete forelimb. Virginia Museum of Natural History collection.

The scan revealed a tiny long-necked reptile with a mouth full of teeth, and extremely long and delicate curved ribs. There was even a totally unexpected complete forelimb, with the hand tucked up next to the skull.

The scan of the 2nd specimen was even more surprising:

Video of the microCT scan of the paratype Mecistotrachelos apeoros. Most of the skeleton anterior to the base of the tail is visible, including the pelvis and hindlimbs. Note the hooked position of the toes. Virginia Museum of Natural History collection.

The 2nd specimen included even more of the skeleton, including the hindlimbs and the base of the tail, even though the neck and skull were not as well preserved. The hind foot is curved into a grasping pose, hinting at arboreal habits.

In the mid-2000's there was no available image stacking software (at least not that we could afford), so one of my jobs was to stack the CT scan slices by hand, to generate a single image of each specimen that we could use in the publication. Nick used these images to make drawings of the specimens:

So, what's up with crazy elongate ribs? Fortunately this is not the only reptile that has them, and there's even a living example! The modern lizard genus Draco, of which there are 41 known species, has elongate ribs that support a membrane used for gliding:

There are also 3 other Triassic reptiles, all in a single clade, that had elongate ribs for gliding, so elongate ribs supporting has evolved on at least 3 separate occasions in reptiles (there are a number of other gliding reptiles that use strategies other than elongate ribs).

In 2007 Nick and several coauthors (including me) published the "Solite glider" as a new genus and species, Mecistotrachelos apeoros (the "long-neck soarer"). As far as I know, this was the first time a fossil species was described based entirely on CT scans.

(As an aside, looking at Karen Carr's artistic interpretation above and the fact that these were tiny animals (the skull is only 2 cm long), it's not lost on me that basically Mecistotrachelos is a tiny teacup dragon that could curl up in the palm of my hand!)

Mecicstotrachelos has several anatomical oddities compared to other gliders. One is the long neck. Other rib gliders have short necks, and it was long assumed that this was necessary to maintain stable flight (most long-necked birds, like herons, curve their neck into a s-curve when flying). But it looks like Mecistotrachelos might not have been able to bend its neck into a tight "S", so it probably flew with its neck relatively straight.

Other rib gliders also have ribs that are generally straight close to the vertebrae, then curve in a single plane distally. But in Mecistotrachelos the ribs start curving close to the vertebrae and have compound curves in multiple planes. The first two ribs also have enlarged articular areas where they attach to the vertebrae. We believe that with this combination, Mecistotrachelos could have used its anterior intercostal muscles to change the shape of its wing, changing its flight properties. If it did this independently on each side of its body, it could even use this to control yaw and pitch, making it a controlled flight glider; this mechanism would work a lot like the wing-warping controls in the original Wright Flyer.

Shortly before I left VMNH to come to the Western Science Center Nick and I secured a grant from National Geographic to do further excavations at Solite. A few weeks after I left, two more Mecistotrachelos specimens were discovered, although these have not yet been CT scanned:

Interestingly, all four known specimens of Mecistotrachelos come from the same bed at Solite, which seems to represent the deepest part of the lake where these sediments were deposited. The only other vertebrate fossils in these beds are fish, including coelacanths that may have approached 1 m in length. The shallow-water sediments in the same sequence are extremely rich in fish, insects, and the aquatic reptile Tanytrachelos, but no gliders have been found there. We think that these four Mecistotrachelos may have been blown off course, and found themselves over the middle of the lake too far to glide back to safety.

The original description of Mecistotrachelos is available on my Publications page.

This post wraps up my special series on ribs (for now). Far from being boring, ribs play a critical role in our survival, and animals have evolved a dazzling number of ways to co-opt their ribs for other functions!

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.