Sinister snails

In spite of the name, being sinistral doesn't mean that you're sinister.

As I mentioned last week, I'm currently immersed in gastropods as we prepare for the opening of our new exhibit, Life in the Slow Lane: The Secret Lives of Snails and Slugs. The exhibit isn't specifically about paleontology, but we are including a large number of fossil snails. One of my tasks for the exhibit is selecting which specimens to display, and confirming their identifications, locations, and life cycle/habitat/age.

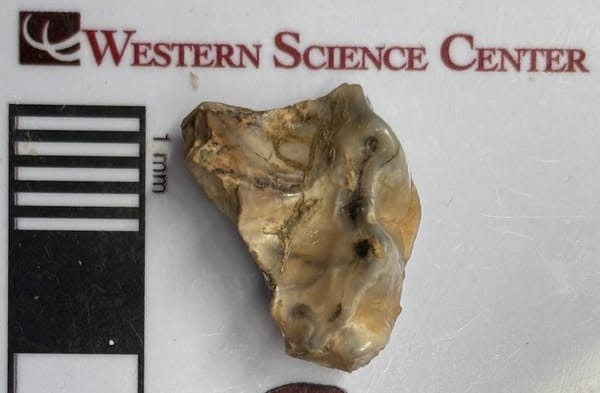

The Western Science Center has a small collection of fossils from the early Pleistocene Waccamaw Formation from North Carolina that includes several gastropods. It includes a single whelk (above), and I was on the fence about whether to include it in the exhibit. As you can see, it's pretty badly broken. It's the only Pleistocene whelk in our collection, but we have much nicer modern ones as well as several nice Pliocene examples. I was leaning toward excluding it, but went ahead with the identification to update our collections record (just because a specimen isn't on exhibit doesn't mean we toss it; even incomplete specimens provide critical data). But once I looked at the shell critically, I identified it as Sinistrofulger contrarium, and that species is special; back into the exhibit it goes!

One of the things that makes this broken shell important for our exhibit is that Sinistrofulger contrarium is the presumed ancestor of the lightning whelk Sinistrofulger perversum, which is common today in the west Atlantic/Gulf of Mexico/Caribbean Sea. We have a modern example for the exhibit:

But besides the possible ancestor - descendent relationship, Sinistrofulgur is an interesting genus in its own right. Below is Sisistrofulgur beside another modern whelk from our collection, Fulguropsis:

The apertures of these shells open on opposite sides! Fulguropsis, on the right, has what is called dextral coiling, because when viewed in this orientation the aperture opens on the right side of the shell. When the aperture opens on the left, it's referred to as sinistral, which is the source of the name Sinistrofulgur.

Whether a snail will have dextral or sinistral coiling is determined when the snail embryo consists of just four cells, and is mostly controlled by a single gene. Generally, except for the coiling direction, both dextral and sinistral embryos will grow up normally, but as adults there is a catch: because the soft anatomy is also asymmetrical, it's very difficult for dextral and sinistral snails to mate with each other. That means there's a strong selective pressure to coil in the same direction as other members of your species. For whatever reason, almost snail species (~99%) are dextral. There are only a handful of species that are normally sinistral; among the several dozen whelks in the family Busyconidae, species of Sinistrofulgur are the only ones that are sinistral.

But the Waccamaw Formation included another oddity:

This is a cone snail, a group famous for their extremely toxic venom, and (in modern forms) their strikingly colorful shells. But a quick look at this specimen shows that it, too, is sinistral. This species, Conus adversarius, is the only known sinistral member of the family Conidae, a group with over 800 species! Unlike Sinistrofulgur, Conus adversarius seems to have left no sinistral descendants, with the lineage apparently going extinct at the end of the Pleistocene.

So that sets up an interesting correlation: the only sinistral whelk ever and the only sinistral cone ever both appear at about the same time in the late Pliocene, in roughly the same place (southeast Atlantic coast/Gulf coast of the US). Was there something going on at that place and time that selected for sinistral shells (keeping in mind that all the other contemporary species in these same deposits were dextral)? Or is it simply a wild coincidence (because contrary to popular belief, correlation and causality are not the same and coincidences do happen)? This is an intriguing paleontological question that we may never be able to answer.

There is an excellent and more detailed discussion of dextral vs. sinistral coiling at the excellent Digital Atlas of Ancient Life.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.