Slipper snails getting busy

Snail reproduction is wild! Some species transition as a normal part of their life cycles.

Our next exhibit, "Life in the Slow Lane: The Secret Lives of Snails and Slugs" opens in one month. One of the reasons we chose to do an entire exhibit on snails is their bewildering variety of habitats, life cycles, ecological roles, and morphologies. One of the many groups highlighted in the exhibit are the slipper snails.

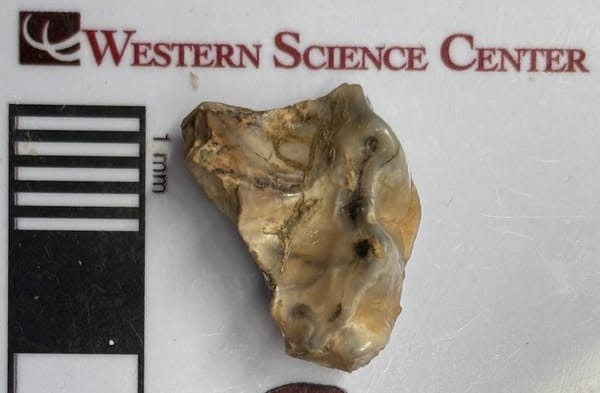

Slipper snails (Family Calyptraeidae) are found today worldwide in tropical and temperate waters. In the exhibit we'll have several modern and fossil specimens, including Pleistocene examples of the extant species Crepidula onyx from Ventura County, California. At the top is a fairly large example in dorsal view, with the ventral view of the same specimen below.

The ventral view shows how slipper snails get their name. The aperture has a large shelf ("deck") that in the living snail separates the foot below from the viscera above. This gives the shell a vague similarity to a bedroom slipper (use your imagination!).

Young slipper shells are able to move around a bit, but as they grow they will permanently attach themselves to most any available hard surface. And it turns out that, for some species including C. onyx, one of the favorite hard surfaces to colonize is other C. onyx shells! In the dorsal view, notice that much of the shell is stained orange but that there's a large ovoid patch that has no staining? That's almost certainly where another C. onyx was attached. Then the second shell became another surface that can be colonized by another snail. And so the stacks grow:

The stack above has five C. onyx stacked one on top of another. Modern stacks of C. onyx have been reported with up to 16 shells! But there's even more to the stacking story.

The shell at the bottom of the stack that starts things off is a large female snail. Typically the snail that colonizes on top of her is a smaller, younger male, that then has easy mating access. But as the male grows larger, it will eventually change sex to a female, and be colonized by one or more males. Crepidula are sequential hermaphrodites, which start their life cycles as males but then transition to females as they get older and larger. So the Crepidula stacks will have older females at the bottom (in large stacks the bottom snails may have already died of old age), young males at the top, and a few in the middle that are in the process of transitioning from male to female. Given typical sizes at transition, in the stack shown above, the top snail was probably male, the 2nd and 3rd may have been transitioning, and the bottom two were probably females. The large shell at the top of the post was almost certainly a female, as male C. onyx are rarely longer than 3 cm.

The slippers are just one example of the incredible diversity in snail reproduction. The shells in this post will be among the specimens on display in "Life in the Slow Lane" when we open on October 25. If you're in Southern California try to visit us for more exciting snail information.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.