Sloth armor

Vertebrates have a long history of armor-plating themselves with bones embedded in the skin. These are called osteoderms - literally "bone skin" (but it sounds so much cooler in Greek). While many vertebrate groups have osteoderms, they aren't something mammals have really adopted, with the exception of one group - the xenarthrans.

The Xenarthra are an order of mammals native to South America, with lots of skeletal anomalies that set them apart from other placental mammals (the name Xenarthra is a reference to a unique vertebral articulation). As it turns out, the xenarthrans also include two groups that have osteoderms, and they apparently evolved them independently of one another. The Cingulata is a large group that includes the armadillos, pampatheres, and their relatives, all of which have osteoderms. The other group are the mylodontids, a family of ground sloths in which only a few genera had osteoderms. That's right–there were armored sloths!

Unlike the armadillos, sloth osteoderms are not connected to one another. Instead, they are embedded in and surrounded by skin. As skin doesn't usually fossilize, when the animal dies and the skin rots the osteoderms fall out and scatter, and so don't get preserved in place on the skeleton. In many projects the osteoderms are recovered through screen washing.

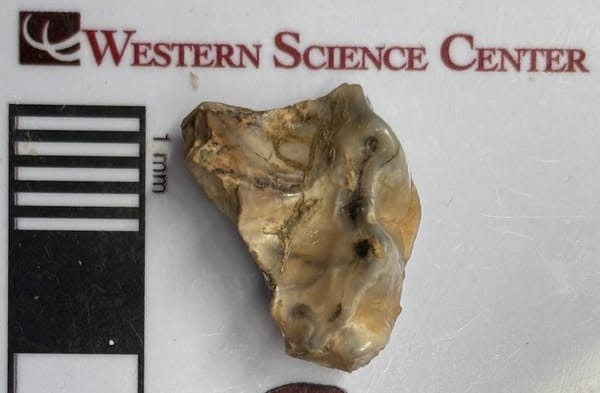

This is how most osteoderms were recovered during the large-scale excavations that took place during the construction of the Diamond Valley Lake reservoir in the 1990s. That effort produced more than 500 osteoderms from the ground sloth Paramylodon harlani, one of which is shown at the top of the page.

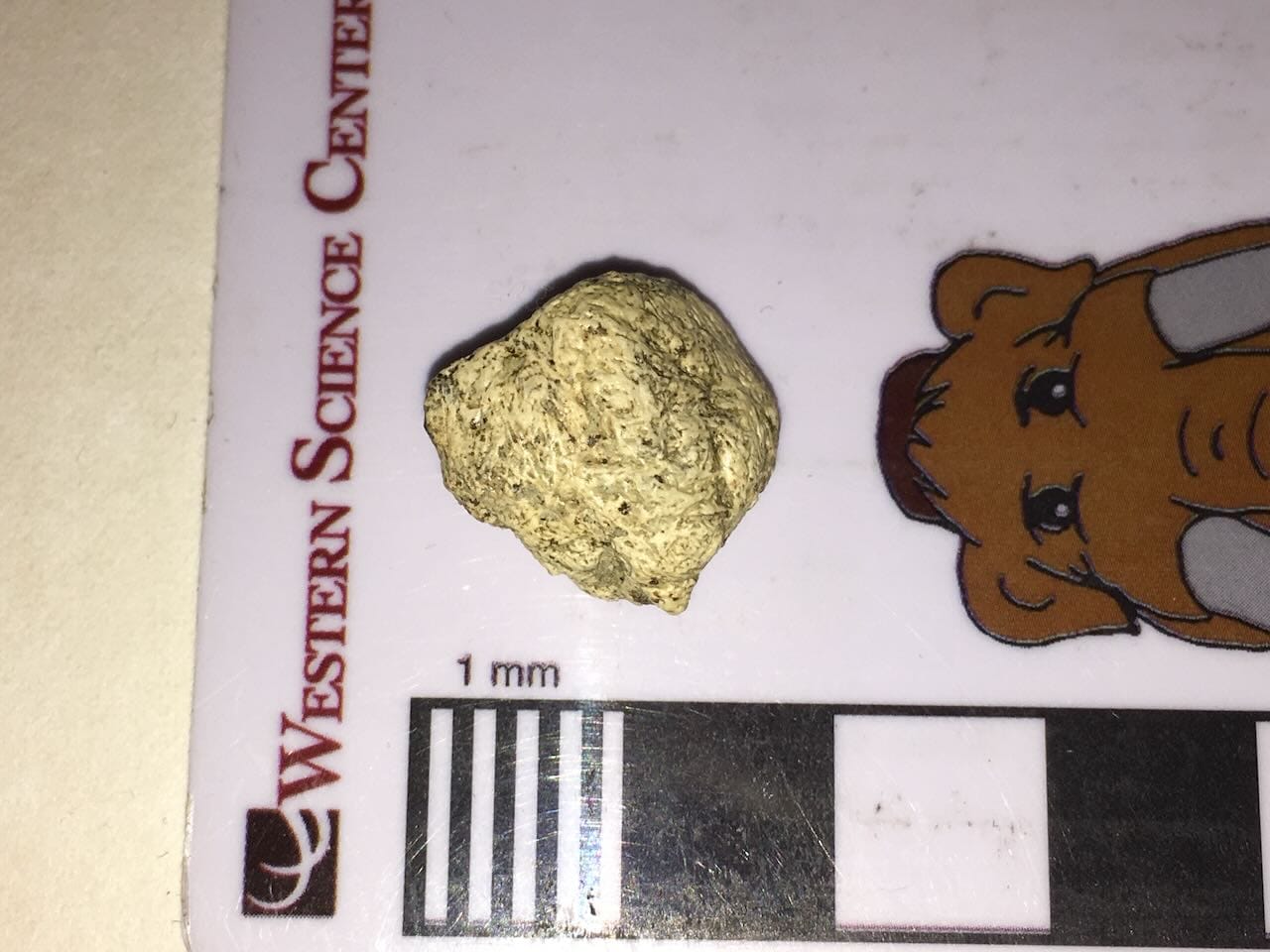

The first thing that jumps out is that even though Paramylodon is a rhinoceros-sized animal, the osteoderm is small, only a little over 1 cm across. That's typical of the armored sloths, although the small size is made up by the vast number of osterderms. The surface shown here is the outward-facing side, but it would not have been visible in the living animal, as skin would entirely cover this surface. That's been confirmed in mummified skin sections of the South American sloth Mylodon, which have the osteoderms still embedded. The internal side of the osteoderm (shown below) is somewhat smoother, and convex across its surface. There is a great deal of variation in the size and shape of the individual osteoderms, but they all typically share these general characteristics.

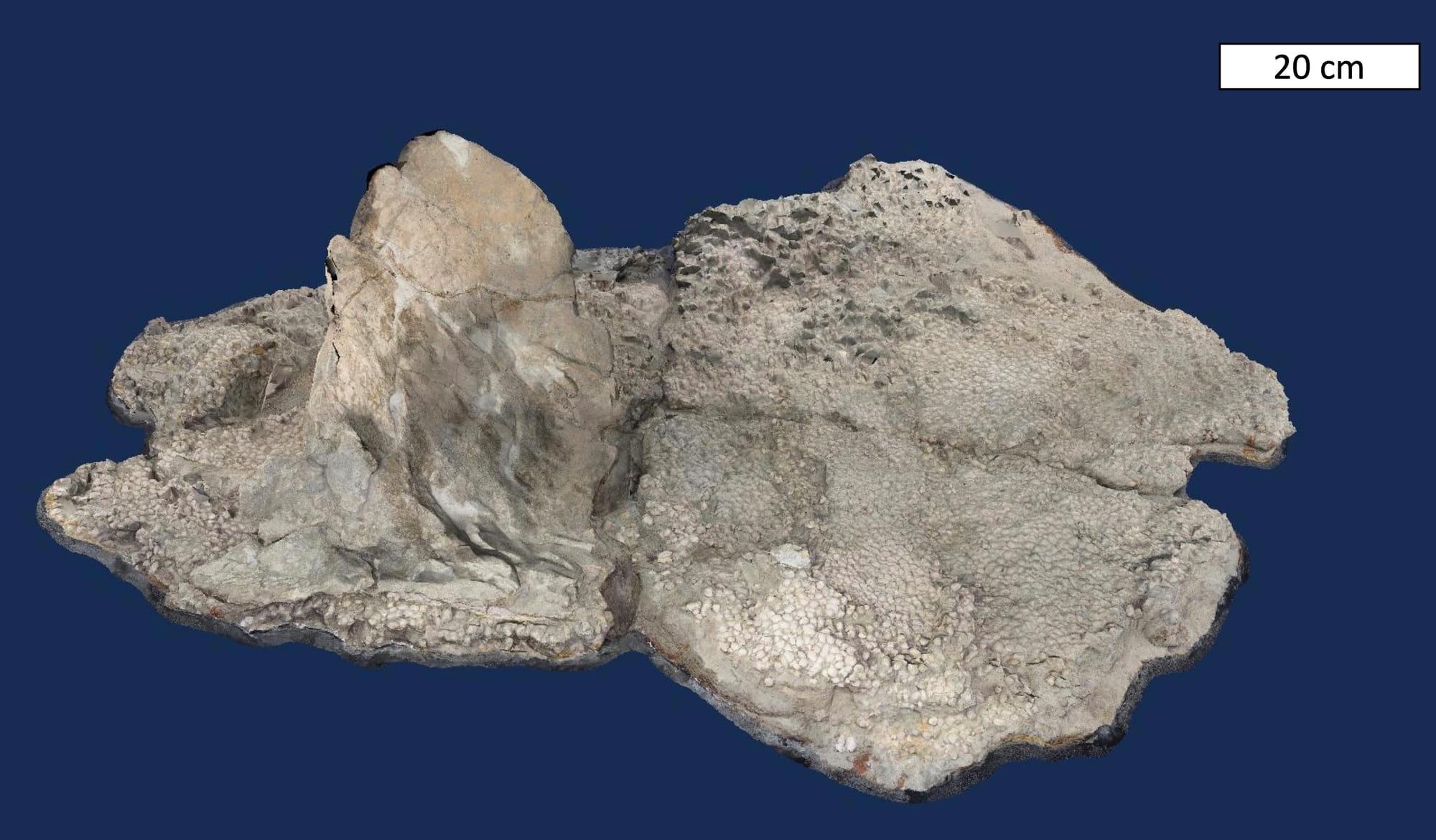

Even though sloth osteoderms are usually isolated, sometimes we get lucky. In 1960, a large segment of fossilized skin with osteoderms and a fragment of the pelvis was recovered at Anza-Borrego State Park in California, giving us a better idea of how the osterderms functioned.

This is the interior surface, so we're looking at the underside of the skin, as if it's been peeled back. The pebbly texture across the surface are all individual osteoderms; there are hundreds of them! And even though they are not fused to each other, they are densely packed to form a remarkably continuous armor layer hidden just below the skin.

Anza-Borrego State Park has conveniently uploaded a 3D model of this specimen for viewing on SketchFab (unfortunately, it's not downloadable):

Even though there used to be armored sloths, there were not very many species of them. According to McDonald (2018) osteoderms have only been reported in 7 genera, and 5 of these are closely related members of the family Mylodontidae. (The other two, Eremotherium and Megatherium, are related to each other in a different family, but there is some question in each case as to whether or not the osteoderms actually come from these genera.) But it seems that at least one group of sloths rediscovered the time-honored vertebrate method of armor-plating yourself with bone, and embraced it wholeheartedly.

Reference: McDonald, H. G., 2018. An overview of the presence of osteoderms in sloths: Implications for osteoderms as a pleisiomorphic character in Xenarthra. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 25:485-493.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.