Snails on the wing

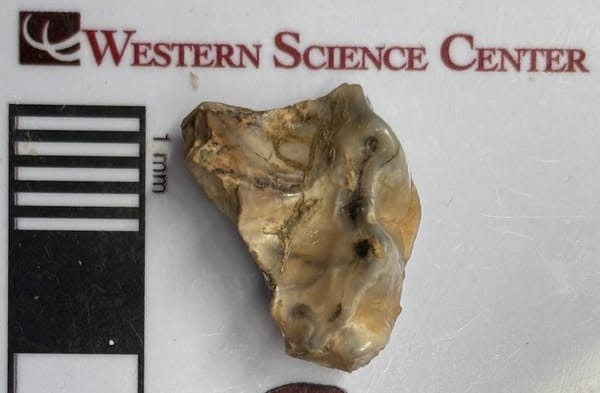

In our current exhibit "Life in the Slow Lane" one of the displays features fossil snails recovered from Pleistocene sediments during the Diamond Valley Lake excavation. Of the roughly 100,000 fossils recovered from DVL, over 4,000 were snails. These were pretty much all very small freshwater and terrestrial snails. One of the largest, with a shell nearly a whopping 1 cm in diameter, is the Marsh ram's horn snail Planorbella trivolvis.

P. trivolvis and other members of its family, the Planorbidae, are air-breathing freshwater snails that feed on detritus and phytoplankton. Members of the family are planispiral, meaning the shell coils in a flat plane making a disk rather than a cone. Unusually, they are also sinistral, meaning the shell aperture opens on the left side when the apex is at the top. The vast majority of snails are dextral, with the shells spiraling the other direction.

P. trivolvis is an extant species that ranges throughout North America from Alaska to Florida, and has also managed to reach Dominica and South America. This is an interesting distribution given that the species is tightly tied to freshwater and individuals don't seem to have large ranges. So how exactly have they managed to reach so many places?

An interesting study by Martin et al. (2020) found that populations of P. trivolvis on the west coast showed greater genetic similarities with their neighbors to the north or south than to the east or west. Even populations separated by hundreds of miles and in different watersheds showed evidence of fairly frequent gene flow, as long as they were along a roughly north-south gradient. This pattern follows the flight corridors of migratory birds. The authors concluded that P. trivolvis disperses when eggs or young snails attach to the feathers of waterfowl when they stop for a rest, and then are carried by the birds to a new location. Interestingly, the genetic differences are greater within a watershed than between watersheds on a north-south line, regardless of distance, suggesting that the snails move more frequently and quickly by attaching to birds than they do crawling upstream or downstream. There is plenty of direct evidence of aquatic snails attaching themselves to birds and being carried to new locations. But it seems that, at least for P. trivolvis, this is their primary means of spreading to new locations.

"Life in the Slow Lane" is currently open at the Western Science Center in Hemet, CA, and will remain open through May.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.