That belongs in a museum!

This year (2026) marks the 20th anniversary of the opening of the Western Science Center. To commemorate this event, each month I'll be doing one post that specifically related to some aspect of the museum's history.

A lot of California politics and planning revolves around water. Much of the state's population lives in areas that depend on reservoirs and water piped in from other locations. That means that, in addition to droughts, our water supply can be vulnerable to disasters like earthquakes, which can break aqueducts and pipelines. So California spends a lot of time and money planning and constructing pipelines and reservoirs.

In 1989 the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) began planning for a new, very large reservoir in Riverside County near the city of Hemet. The new reservoir, Diamond Valley Lake (DVL) would be located west of the San Jacinto and San Andreas Faults, and therefore pipelines connecting the reservoir to coastal cities wouldn't have to cross the faults and would be less likely to break in an earthquake. The reservoir would be formed by flooding Diamond and Domenigoni Valleys, and would require the construction of three huge earthen dams and the relocation of the pre-existing San Diego Canal. To reduce expense, the dams would largely be built from local materials excavated from the valleys.

Any major public works project requires addressing various concerns before it can move forward, including for example environmental issues. Various federal and state laws also require developers to remove and properly care for archaeological remains, especially significant in this project since people have lived in Diamond Valley for at least 11,000 years. But unlike most states, California also protects fossil resources, and requires an assessment and mitigation plan for fossils that might be found during construction.

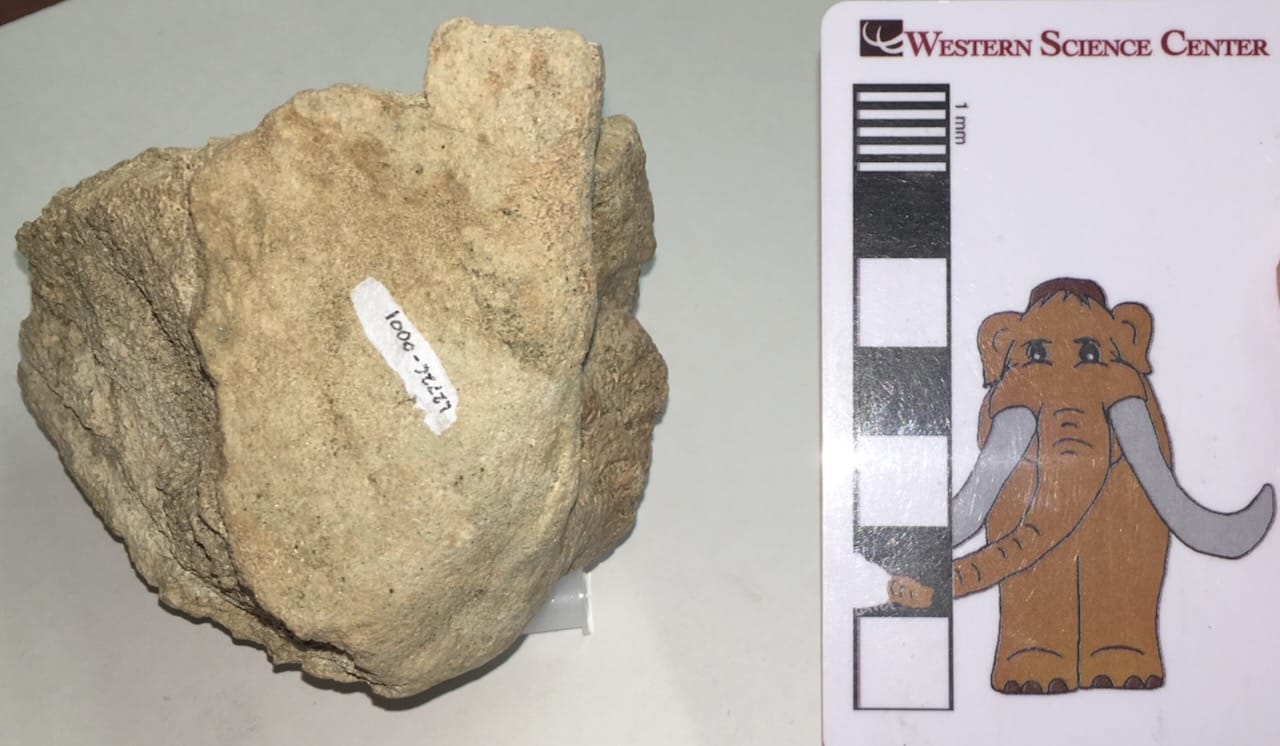

The initial paleontological assessment for Diamond Valley predicted that the likelihood of finding fossils in the Valley were quite low. This didn't sit well with paleontologist Kathleen Springer, then at the San Bernardino County Museum. Her experiences in other inland locations suggested that, given how deep the Diamond Valley excavations would go, the odds of finding fossils was very high. She sent a letter to MWD expressing these concerns, and MWD listened. A mitigation plan was put in place to ensure the preservation of any fossils that were discovered. Construction planning started in 1993, and almost immediately fossils were found near the old San Diego Canal:

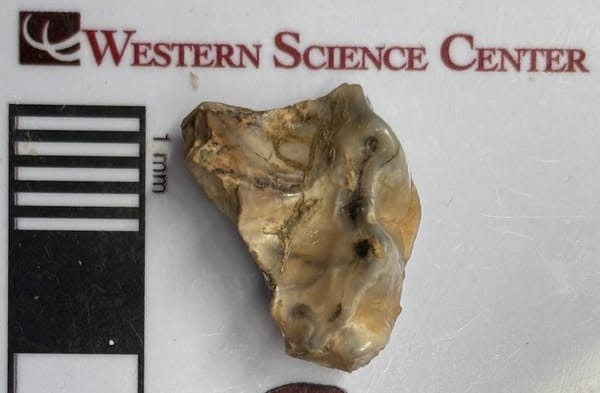

These very scrappy remains were mostly identified as "large mammal", but one of them preserved some useful features:

It turns out that this fragment is part of the shoulder socket from the right scapula of a proboscidean. In 1998, paleontologist Eric Scott recognized that it came from a large mastodon (shown below superimposed on an image from Olsen 1972):

As construction got underway and fossils and artifacts began to be recovered, some of the local residents took notice. Fossils had been recovered in various parts of Riverside County for many years, but with no large fossil repository in the county the material went to various other institutions, some of them far from the area. A group of local leaders, the Hemet/San Jacinto Action Group, wanted to ensure that the people living in Riverside County had an opportunity to enjoy and learn from these collections. To that end, in 1995 they proposed to MWD that a research museum, the Western Center for Archaeology and Paleontology, be established near the lake to house and study the new specimens. Within a few months State Senator David Kelley established the California State Senate Working Group on the Western Center for Archaeology and Paleontology to study the proposed museum, and by the end of 1996 received $25,000 from the University of California-Riverside and the State of California to begin initial planning, followed by an additional $250,000 in 1997. In 1998 California allocated $5 million to begin construction, and the Hemet/San Jacinto Action Group formed the Western Center Community Foundation (WCCF), a nonprofit group to build and operate the museum. Hemet developer Howard Rosenthal was the first president of the WCCF, and founding members included Senator Kelley, Clayton Record from MWD, and Raymond Orbach from UC-Riverside, as well as other community leaders from the area. Additional state funds followed, and in 2001 WMD and WCCF reached a lease agreement to build the museum on land near the DVL East Dam and to designate the new museum as the repository for the DVL specimens.

Things moved quickly from that point. Architectural contracts were signed in 2002, and with additional state grant funds coming in, the ceremonial groundbreaking occurred in June 2003. Construction started in earnest in 2004:

The museum finally opened to the public on October 15, 2006, although some of the exhibits weren't completed until 2007. In 2009 the WCCF Board elected to change the name of the museum to the Western Science Center, which has been our operational name ever since.