The Nine Sisters

Each December, Brett and I try to spend a few vacation days in the small California coastal town of Morro Bay. Morro Bay (the town) is named for Morro Bay (the bay), an estuary than runs parallel to the coast for about 6 km. Morro Bay is the only protected harbor for small boats between Monterey and Santa Barbara and supports a thriving marina and fishing industry. The entrance to the harbor lies at the north end of the estuary and is marked by (you guessed it) Morro Rock.

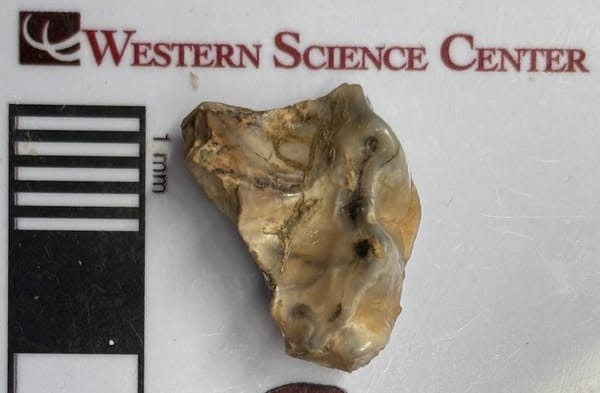

At 176 m tall, Morro Rock is an imposing site. To stand for so long against the battering of the Pacific Ocean it has to be made of something pretty durable. At one time Morro Rock was quarried to provide rock for breakwaters and other uses, and pieces of it can be found all over town (the Rock itself is now protected as a landmark and a peregrine falcon nesting sanctuary). Up close, Morro Rock is made of this:

This is an igneous rock called dacite. The white angular chunks are crystals of plagioclase feldspar and quartz, minerals that are high in silica and sodium. There are also darker colored minerals that are rich in iron and magnesium and fairly low in silica, such as biotite, hornblende, and pyroxene; these contribute to the dark gray overall color. In terms of composition, dacite is considered an intermediate rock, meaning that its composition is intermediate between high-silica rocks such as granite and low-silica rocks such as basalt.

This rock has a mixture of large crystals that are big enough to easily see, and small crystals that can only be seen with a microscope. This mixture of large and small crystals is referred to as porphyritic, and it’s important to note because there are only a few ways that molten magmas can turn into porphyritic rocks. Basically, the bigger a crystal is, the longer it takes to form, which indicates the magma cooled very slowly. If the crystals are tiny, it indicates the magma cooled fast. A porphyritic rock has both, so it needs to spend a long time underground slowly cooling, which gives time for the large crystals to grow. But then the partially solid magma has to be brought quickly to the Earth’s surface (or close to it), chilling the remaining molten magma. In other words, a volcanic eruption – Morro Rock is the remnant of a volcano!

To be clear, Morro Rock is not the volcanic mountain itself. Rather, it is a cooled plug of magma that was underneath the volcano. Dacite has a very high viscosity, so it will tend to clog up the volcano. If there’s still a lot of magma coming up from below, it might burst through the dacite plug in a pyroclastic explosion (think Mt. St. Helens or Krakatoa). But eventually the heat source fades, and the last dacite plug is left in place. In the case of Morro Rock, its dacite was much harder than the surrounding rocks, so they eroded away leaving the dacite plug behind, standing above the landscape.

But that raises another mystery; what is Morro Rock doing there, right on the coast? Intermediate composition volcanoes are associated with tectonic subduction zones such as we have off the coasts of northern California, Oregon, and Washington today, but those volcanoes occur many kilometers inland; look as how far Mt. St. Helens is from the coast.

In a subduction zone oceanic crust slides underneath thick continental crust and is eventually pushed into the hotter underlying mantle. When is gets deep enough, parts of each crust can melt, forming intermediate-composition magmas that make their way back to the surface and erupt as volcanoes. Because the ocean crust is 10‘s of kilometers thick, and the continental crust can reached over 100 kilometers thick, the ocean crust has to travel awhile before it gets deep enough into the mantle for melting to start, so the volcanoes show up on the continent as much as 100 km inland. So how did Morro Rock form so close to the coast?

It’s actually an even greater problem than that, because Morro Rock is not alone! It is actually the westernmost example of a linear chain of dacite volcanic plugs called the Nine Sisters that stretch inland about 15 km to the southeast from Morro Bay. There are actually more than 20 of these volcanic features along the line, plus a submerged seamount offshore; the name refers to the nine largest peaks in the chain. Brett and I drove into the hills near San Luis Obispo where we could see eight of the nine sisters from one spot; Cerro San Luis was partially hidden behind a hill in the foreground and Islay Hill, the easternmost of the nine, is out of view to the right:

All of the Nine Sisters were formed around 20-25 million years ago; there was no volcanic activity in the area before or since. So something different was happening here at that time. The answer seems to be related to the peculiarities of subduction off the California coast in the Miocene.

Oceanic crust is formed along ruptures called mid-ocean rifts. When a continent pulls apart, magma wells up forming ocean crustal rocks in the rift. As the rift widens, new ocean crust continues forming at the center of the rift, with the older crust moving to the side. As the ocean crustal rocks continues moves away from the mid-ocean rift, it cools and gets thicker. Eventually this old, cool ocean crust will subduction under younger ocean crust or under less dense continental crust, and be forced back into the mantle.

But around 25 million years ago something changed in California. As the North American plate continued drifting to the west, it ran over the Pacific mid-ocean rift where new ocean crust was being formed. Remember up above I said it takes awhile for the subducting ocean crust to get deep enough to reach the mantle and heat up, and that’s why the volcanoes are so far inland? At the mid-ocean ridge the ocean crust is very thin, and it’s still hot. It doesn’t have to be pushed down very far to reach the mantle and start to melt; it’s practically there already. So it only has to travel a short distance before volcanoes make their way to the surface, and we end up with a string of volcanoes right next to the coast. But it couldn’t last. The North American plate continued moving west and eventually the mid-ocean ridge was completely subducted, cutting off the source of magma and allowing the volcanic plugs to solidify.

The Nine Sisters are a major geographic feature of this part of California. Their unusual topography and rock chemistry impacts the biomes that are found in this area, and in turn has impacted the way people live in these areas for thousands of years, and continues to do so. And it’s all because a transient quirk in the geometry of tectonic plates that occurred 25 million years ago.

There is an excellent summary of Nine Sisters geology at the Morro Bay National Estuary Program.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.