Tiny mastodon from the bayou

"That's how, two months after our marriage, my wife and I headed off to prison." Subscribe to read now! Otherwise, the paywall comes down on Friday.

Brett and I were married in June of 1994, and spent the summer honeymooning in various national parks across the west. Finally late in the summer we drove to Baton Rouge where I would start my 4th year of my PhD program, and Brett would start a job as a lab technician for my advisor, Judy Schiebout. About a week after we arrived in town, Dr. Schiebout called us into her office with an assignment. She had received a call from the Louisiana State Penitentiary that a prisoner there, Kerry Van Welch, had found some possible fossil bones while removing a hillside for construction. We were tasked with going to the prison to evaluate the material, and if it turned out to be significant, see if we could arrange to excavate further. That's how, two months after our marriage, my wife and I headed off to prison.

Louisiana State Penitentiary (commonly known as Angola) is located on a huge tract of land in the Tunica Hills. As I discussed last week, this area is covered with a thick blanket of wind-blown glacial clays (loess), which contain quite a lot of Ice Age fossils. So we had high hopes that the specimens would in fact turn out to be fossils, and we weren't disappointed; sitting in the warden's office were numerous bone fragments and a mastodon tooth.

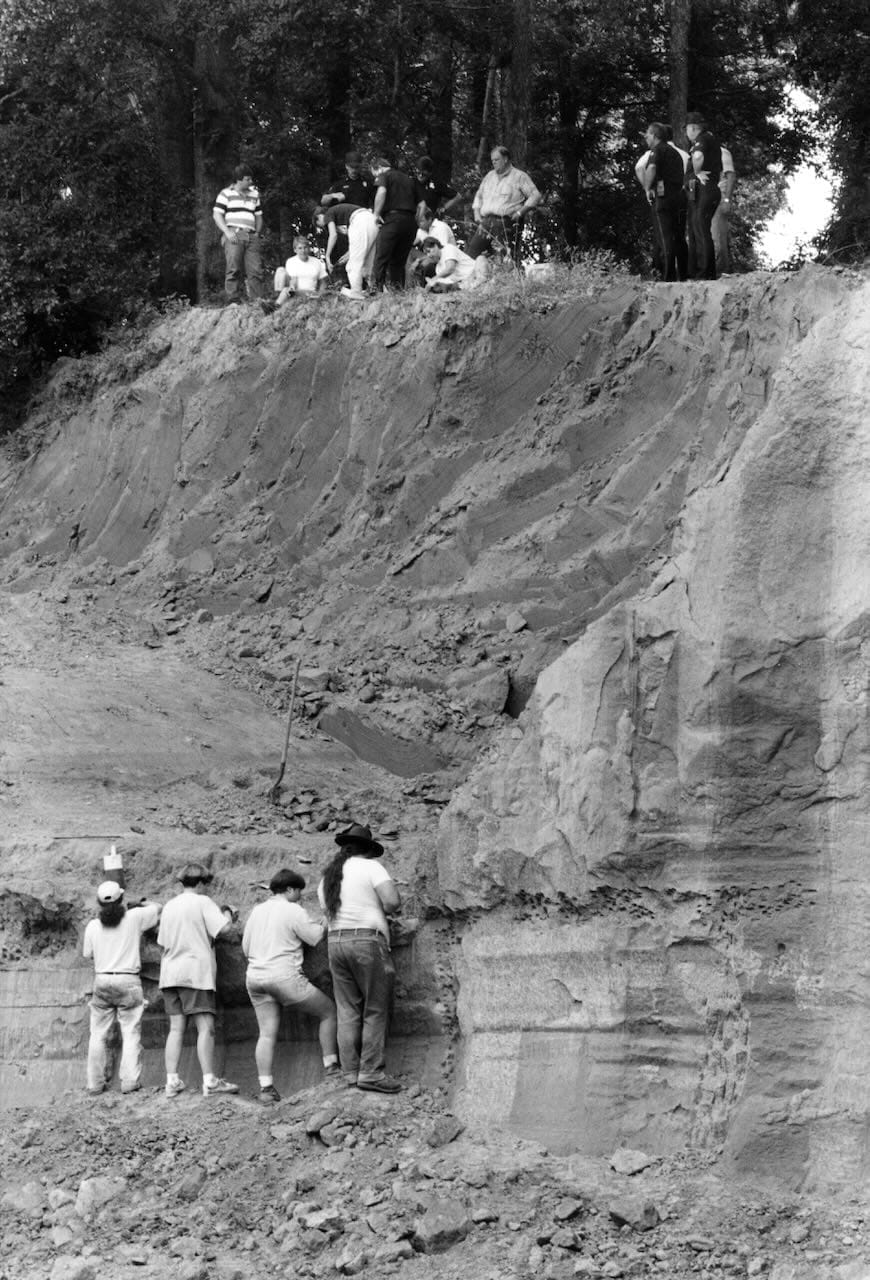

After some negotiations with the prison administration and guards, we arranged to bring a crew of LSU students and volunteers to the prison each day for several weeks to monitor the hillside removal for additional bones. This received a lot of local media attention, and was my first real experience dealing with the press. (Incidentally, probably the best article about the excavation was by Michael Glover in The Angolite, Angola's inmate-published prison magazine.)

After several weeks and the recovery of several bones, things got exciting again when one of the crew members found human bones at the top of the hill, 6-7 meters about the mastodon! We called in LSU's archaeologists to handle that find, and ended up with the unusual situation of simultaneous, unrelated archaeological and paleontological excavations on the same hillside, which is what's shown in the photo at the top of the page. The human remains turned out to date from the early-mid 1800's when Angola was a cotton plantation worked by slave labor. Only one partial human skeleton was found; after excavation and examination, the remains were reinterred in a nearby location.

We didn't find our hoped-for mastodon skull or compete skeleton, but we did find a number of very delicate limb elements, some tusk fragments, and two upper teeth. We did some minimal cleaning and stabilizing, and then put the bones away. I was busy with my doctoral research on fossil whales (and at the time knew almost nothing about mastodons), other students had their own projects, and we were gearing up for a major excavation of a Miocene site in western Louisiana. So we figured some future student would pull the remains and write them up. Twenty years went by...

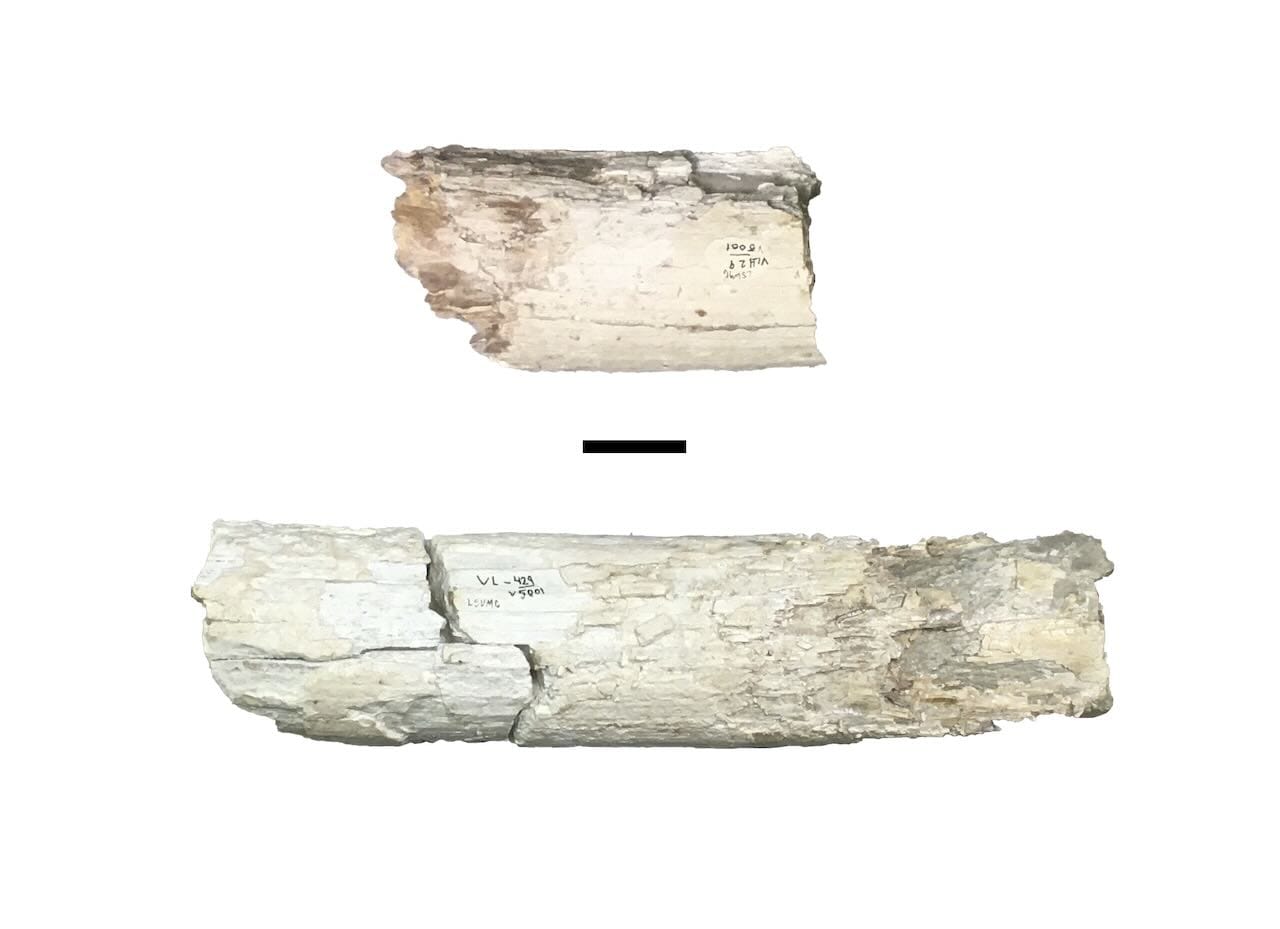

By 2016 I was working at Western Science Center and had become immersed in mastodon research. I was particularly interested in tooth proportions, so Brett and I took a summer roadtrip across the midwest to measure mastodon teeth, including a stop at LSU. We found the Angola mastodon in pretty much the same state as when I graduated in 1998, but we got measurements off the teeth. With my newly acquired mastodon knowledge we were also able to determine that the teeth were upper 3rd molars, and that at the time of death the animal had been mature and (very roughly) around 40 years old. Based on the small diameter of the tusks (below), it was likely also a female mastodon.

Brett and I only had one day at LSU, and lots of teeth to measure, so we didn't have time to examine the other remains of the Angola mastodon. Another four years went by...

By the end of 2020 I was committed to writing the proboscidean chapter for Vertebrate Fossils of Louisiana, and decided this would be a great opportunity to take a closer look at the Angola mastodon and more widely announce its presence to the scientific community. But of course, this was during the COVID shutdown, and I wasn't about to fly to Baton Rouge. Fortunately, then-LSU undergraduate Connor White stepped up. Through a long series of Zoom calls he went through the entire LSU proboscidean collection with me, while I taught him mammoth and mastodon anatomy. When we got to the Angola mastodon, we worked together to identify and assemble the various fragments. In addition to the two teeth and the tusks fragments, we identified most of the right femur, a partial left ulna, and a nearly complete left humerus (below):

The well-preserved humerus is an especially nice find, because it allows us to directly compare the size of this mastodon to other individuals (teeth are notoriously unreliable for this). Compared to 32 other published measurements of American mastodon humeri, only three specimens were shorter than the Angola mastodon's 748 mm!

This makes the Angola mastodon one of the smallest examples known of its species, yet it was found less than 2 kilometers from the gigantic mastodon jugal that I talked about last week. There may have been some giants wandering around the Louisiana swamps during the Ice Age, but they weren't all giants, and we clearly still have a lot to learn about mastodon biology.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.