Western whiptail lizard vertebra

I learned a thing about lizard vertebrae.

Somewhere way back when I was learning anatomy, I dimly recall being taught one of the keys to identifying snake vertebrae was the presence of a zygosphene and a zygantrum. A few weeks ago when I was writing the post on the fossil rattlesnake vertebra, I checked sources to confirm my interpretation of the bone and discovered that, in fact, there are some other reptiles that have a zygosphene! One of these groups is the lizards from the family Teiidae, which include the whiptails and racerunners, such as the six-lined racerunner shown above.

Of course, having learned that teiids have this structure I wanted to see it for myself. The western whiptail (Aspidoscelis tigris) is native to this part of California, but unfortunately we don't have any modern specimens in our reference collections. A check of our database, however, showed that we do have several fossil examples in our collection. It turns out the vertebrae are tiny, only a couple of millimeters long, so it also gave me a chance to try out some microphotography with some new (to me) image-stacking software.

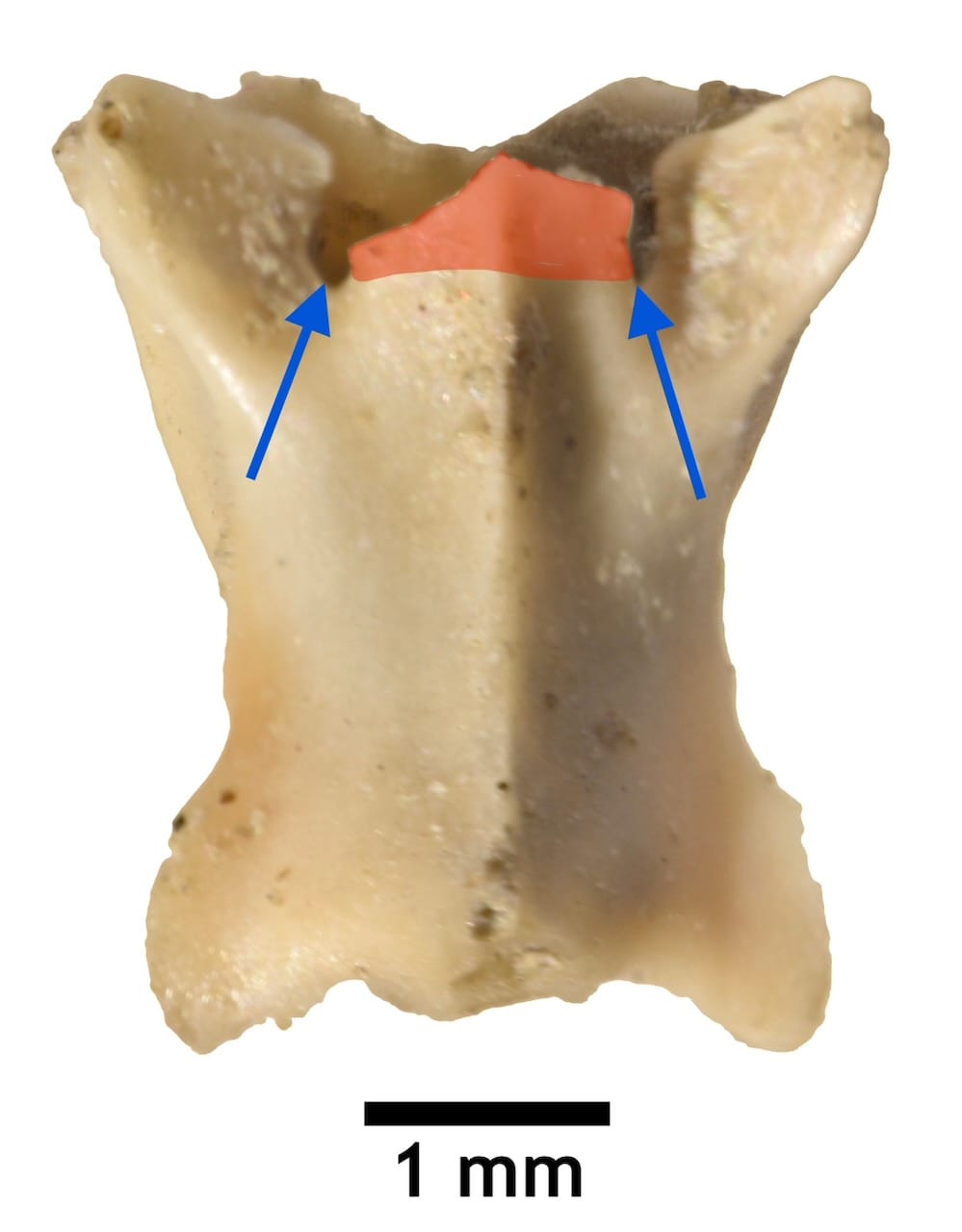

Below is one of the whiptail trunk vertebrae, seen in dorsal view with anterior at the top. Note the scale bar; this vertebra is only about 4 mm long!

Next is a marked-up version of the same image. And, just as the various papers I checked indicated, a zygosphene is present, highlighted in red. The blue arrows are pointing out narrow grooves that separate the zygosphene from the prezygopophyses. This seems to be one of the ways to distinguish this vertebra from a snake's. In the snakes I’ve examined, this notch opens to the side, and so isn’t visible in dorsal view.

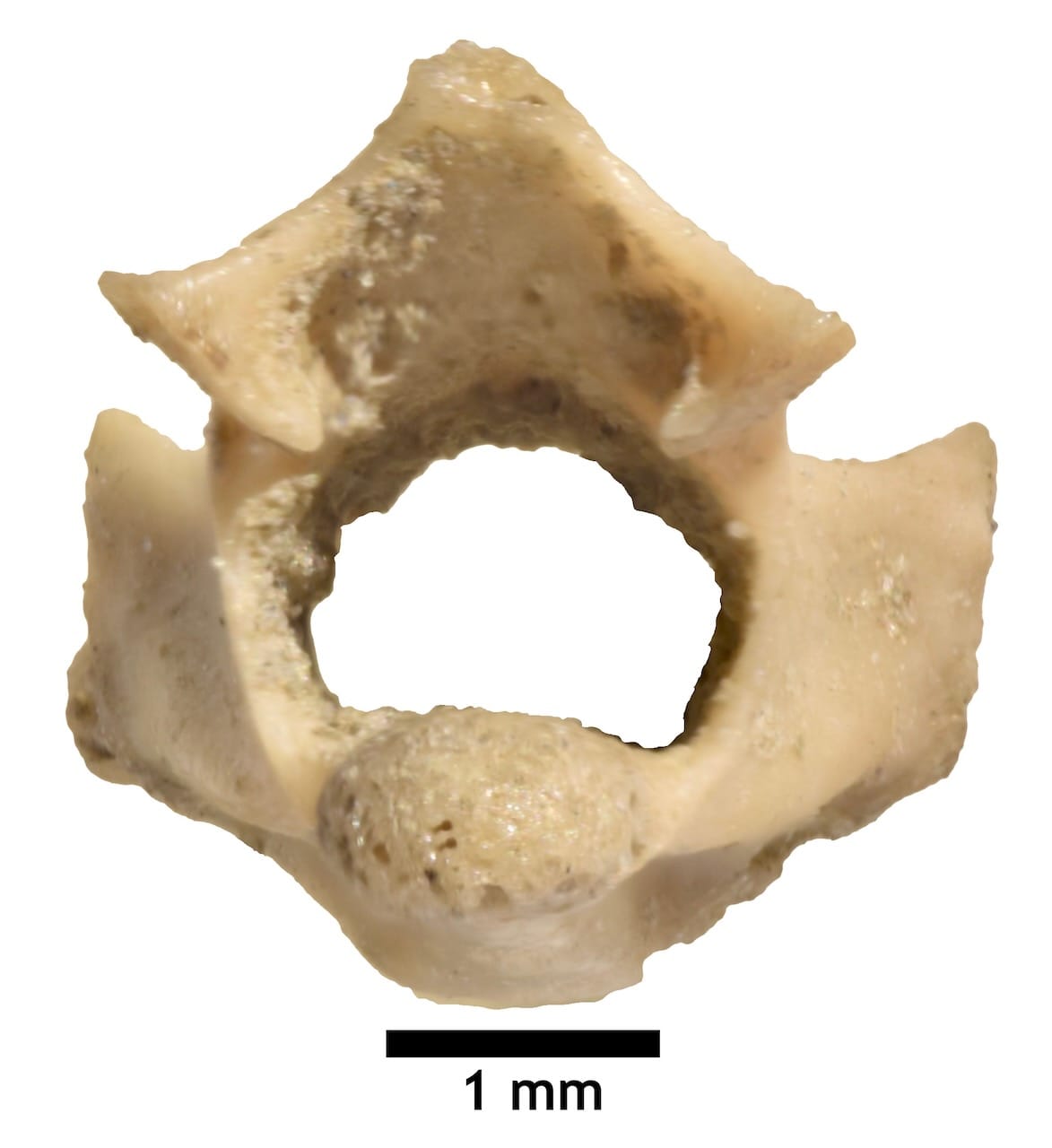

Next we have a posterior view of the same vertebra. Note that there’s no projection (the hypapophysis) projecting down from the bottom of the vertebra. Snake trunk vertebrae typically have a large, prominent hypapophysis.

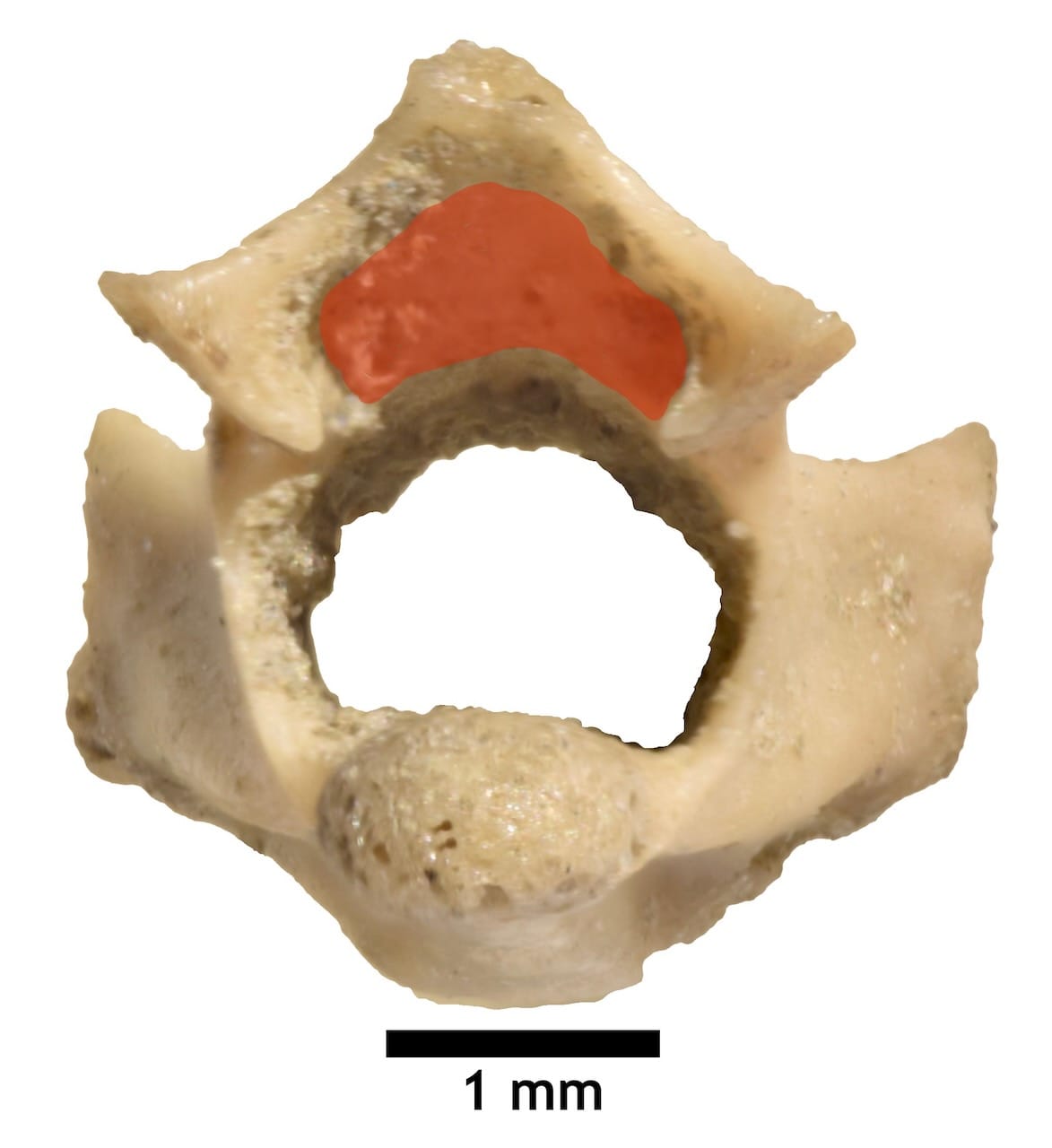

If a vertebra has a zygosphene projecting forward, the vertebra in front of it should have a zygantrum to project into. Sure enough, our whiptail vertebra has a zygantrum, indicated in red below.

While snakes, teiids, and several other groups have a zygosphene-zygantrum articulation, the details of the structure differ in each group, and the groups are generally not thought to be closely related to one another. It seems that this type of structure has convergently evolved several times.

If you like what you're reading, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or leaving a tip. All proceeds go to cover the cost of maintaining the site and supporting research and education at the Western Science Center.