Harvey the Mammoth

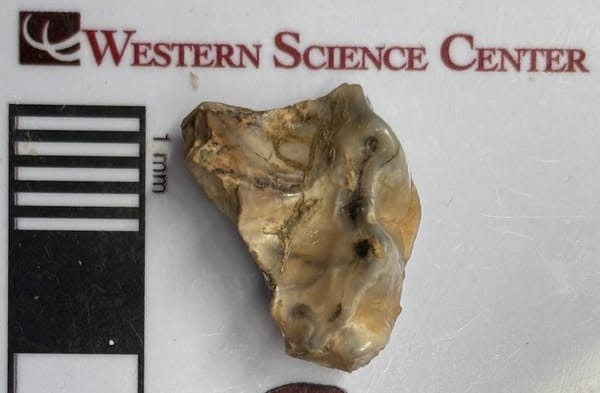

Later this year Western Science Center will be opening a new permanent exhibit (more on that in a future post). One of the highlighted specimens in this exhibit will be the skull of Harvey the Mammoth. Like many of WSC's specimens, Harvey was discovered during a construction project,